Magnetism

42 Magnetic Fields Produced by Moving charges (Biot-Savart Law) and by Currents (Ampere’s Law)

Learning Objectives

- Calculate current that produces a magnetic field.

- Use the right hand rule 2 to determine the direction of current or the direction of magnetic field loops.

How much current is needed to produce a significant magnetic field, perhaps as strong as the Earth’s field? Surveyors will tell you that overhead electric power lines create magnetic fields that interfere with their compass readings. Indeed, when Oersted discovered in 1820 that a current in a wire affected a compass needle, he was not dealing with extremely large currents. How does the shape of wires carrying current affect the shape of the magnetic field created? We noted earlier that a current loop created a magnetic field similar to that of a bar magnet, but what about a straight wire or a toroid (doughnut)? How is the direction of a current-created field related to the direction of the current? Answers to these questions are explored in this section, together with a brief discussion of the law governing the fields created by moving charges and currents.

Magnetic Field Created by Moving Charges

Just like electric field [latex]{\vec{E}}[/latex] is a vector field, the magnetic field [latex]{\vec{B}}[/latex] is also a vector field. The electric field exerts force on a charge [latex]q[/latex], that is [latex]{\vec{F}}=q{\vec{E}}[/latex]. Similarly the magnetic field exerts force on another moving charge. Note that the magnetic field does not exert force on stationary charges. As you know a moving charge is a current, which means a current produces a magnetic field and exerts force on other currents in its influence.

In this part we will focus on the magnetic field generated by an isolated moving charge. To do so, we will determine the magnetic field of a moving charge at a field point [latex]p[/latex] at a particular instant of the motion. This calculation is based on the well known experimental evidence. This evidence was first studied in the experiments conducted by Biot and Savart whose conclusions result in what we today call the Biot-Savart law.

This calculation is similar to the one we did when we studied Coulomb’s law. The experimental evidence suggests that the magnetic field [latex]{\vec{B}}[/latex] is inversely proportional to the square of distance from the source point, that is [latex]B{\propto}\frac{1}{{r}^2}[/latex]

The magnetic field is also directly proportional to the speed of moving charge and to the magnitude of the moving charge [latex]|q|[/latex]. The experiments also showed that the magnetic field is directly proportional to the sine of the angle [latex]{\theta}[/latex] between the charge’s velocity vector and the position vector [latex]{\vec{r}}[/latex] of the field point.

An interesting difference between electric and magnetic fields is that in electric field the direction of the field was along the line joining the source point to the field point but in magnetic field the direction is perpendicular to the plane containing the velocity vector [latex]{\vec{v}}[/latex] and position vector [latex]{\vec{r}}[/latex] joining the source point and field point as shown in figure above.

Putting all the relationships together we can write the equation for the magnetic field created by a moving charge as:

[latex]B=k\frac{|q|v {\sin} {\theta}}{r^2}[/latex] where [latex]k[/latex] is the proportionality constant and it’s value is [latex]k=\frac{{\mu}_0}{4{\pi}}[/latex], and we can write:

[latex]B=\frac{{\mu}_0}{4{\pi}}\frac{|q|v {\sin} {\theta}}{r^2}[/latex]. (Equation 1)

The above equations can not be verified experimentally because it is based on an isolated moving charge and no such charge is possible. You know in electric circuit that a charge can only move if it is part of a complete electric circuit.

In reality, Equation 1 comes from a more complete equation that includes the vectorial product of the vectors [latex]{\vec{v}}[/latex] and the unitary vector [latex]{\hat{r}}[/latex].

[latex]B=\frac{{\mu}_0}{4{\pi}}\frac{|q|{\vec{v}} {\hat{r}}}{r^2}[/latex]. (Equation 2)

The direction of magnetic field can be determined by using the right hand rule 2 (RHR-2). In this case you can point with your thumb in the direction of [latex]{\vec{v}}[/latex] and the curled fingers pointing in the direction of [latex]{\hat{r}}[/latex] give the direction of magnetic field for a positive moving charge. If the moving charge is negative, the direction of magnetic field is opposite to the direction of curled fingers for the positive charge case.

In the case in Figure 42.1 at the point [latex]p[/latex] the direction is outward, that is towards you. The magnetic field has maximum magnitude when the angle between [latex]{\vec{v}}[/latex] and [latex]{\vec{r}}[/latex] is [latex]{90}^o[/latex] and zero when the angle is [latex]{0}^o[/latex].

The real actual experiments were done by Biot and Savart for current carrying conductor called and the summarized version of their experiments is called Biot-Savart law. Here the magnetic field of moving charge is determined for an isolated moving charge and this is truly valid in terms of Biot-Savart law even if no isolated charge is possible.

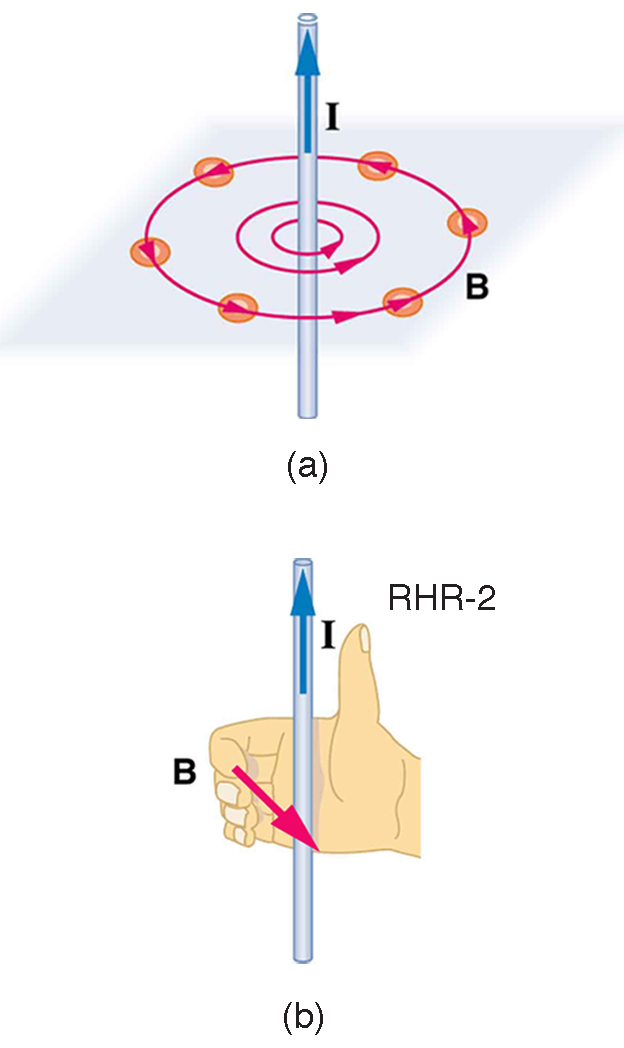

Magnetic Field Created by a Long Straight Current-Carrying Wire: Right Hand Rule 2

If we now generalize and instead of focusing on a single charge we study the effect for a line of current. As noted before, one way to explore the direction of a magnetic field is with compasses, as shown for a long straight current-carrying wire in Figure 42.2. Hall probes can determine the magnitude of the field. The field around a long straight wire is found to be in circular loops. The right hand rule 2 (RHR-2) emerges from this exploration and is valid for any current segment—point the thumb in the direction of the current, and the fingers curl in the direction of the magnetic field loops created by it.

The magnetic field strength (magnitude) produced by a long straight current-carrying wire is found by experiment to be

where [latex]I[/latex] is the current, [latex]r[/latex] is the shortest distance to the wire, and the constant [latex]{\mu }_{0}=4\pi \phantom{\rule{0.15em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.15em}{0ex}}{\text{10}}^{-7}\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}T\cdot \text{m/A}[/latex] is the permeability of free space.

[latex]{\mu }_{0}[/latex] is one of the basic constants in nature. We will see later that [latex]{\mu }_{0}[/latex] is related to the speed of light.) Since the wire is very long, the magnitude of the field depends only on distance from the wire [latex]r[/latex], not on position along the wire.

Example 42.1: Calculating Current that Produces a Magnetic Field

Find the current in a long straight wire that would produce a magnetic field twice the strength of the Earth’s at a distance of 5.0 cm from the wire.

Strategy

The Earth’s field is about [latex]5\text{.}0×{\text{10}}^{-5}\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}T[/latex], and so here [latex]B[/latex] due to the wire is taken to be [latex]1\text{.}0×{\text{10}}^{-4}\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}T[/latex]. The equation [latex]B=\frac{{\mu }_{0}I}{2\mathrm{\pi r}}[/latex] can be used to find

[latex]I[/latex], since all other quantities are known.

Solution

Solving for [latex]I[/latex] and entering known values gives

Discussion

So a moderately large current produces a significant magnetic field at a distance of 5.0 cm from a long straight wire. Note that the answer is stated to only two digits, since the Earth’s field is specified to only two digits in this example.

Ampere’s Law and Others

The magnetic field of a long straight wire has more implications than you might at first suspect. Each segment of current produces a magnetic field like that of a long straight wire, and the total field of any shape current is the vector sum of the fields due to each segment. The formal statement of the direction and magnitude of the field due to each segment is called the Biot-Savart law. Integral calculus is needed to sum the field for an arbitrary shape current. This results in a more complete law, called Ampere’s law, which relates magnetic field and current in a general way. Ampere’s law in turn is a part of Maxwell’s equations, which give a complete theory of all electromagnetic phenomena. Considerations of how Maxwell’s equations appear to different observers led to the modern theory of relativity, and the realization that electric and magnetic fields are different manifestations of the same thing. Most of this is beyond the scope of this text in both mathematical level, requiring calculus, and in the amount of space that can be devoted to it. But for the interested student, and particularly for those who continue in physics, engineering, or similar pursuits, delving into these matters further will reveal descriptions of nature that are elegant as well as profound. In this text, we shall keep the general features in mind, such as RHR-2 and the rules for magnetic field lines listed in Magnetic Fields and Magnetic Field Lines, while concentrating on the fields created in certain important situations.

Making Connections: Relativity

Hearing all we do about Einstein, we sometimes get the impression that he invented relativity out of nothing. On the contrary, one of Einstein’s motivations was to solve difficulties in knowing how different observers see magnetic and electric fields.

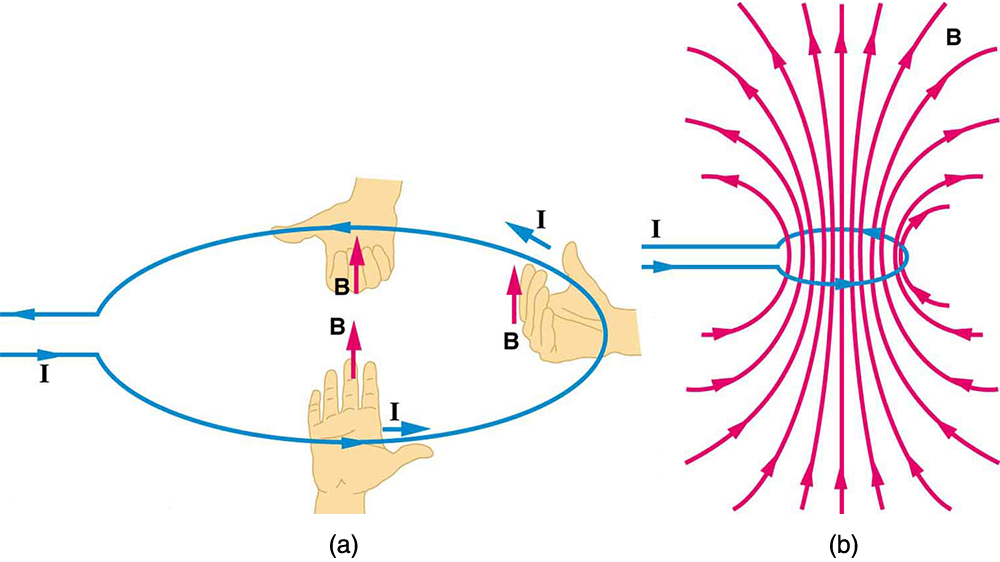

Magnetic Field Produced by a Current-Carrying Circular Loop

The magnetic field near a current-carrying loop of wire is shown in Figure 42.2. Both the direction and the magnitude of the magnetic field produced by a current-carrying loop are complex. RHR-2 can be used to give the direction of the field near the loop, but mapping with compasses and the rules about field lines given in Magnetic Fields and Magnetic Field Lines are needed for more detail. There is a simple formula for the magnetic field strength at the center of a circular loop. It is

where [latex]R[/latex] is the radius of the loop. This equation is very similar to that for a straight wire, but it is valid only at the center of a circular loop of wire. The similarity of the equations does indicate that similar field strength can be obtained at the center of a loop. One way to get a larger field is to have [latex]N[/latex] loops; then, the field is [latex]B={\mathrm{N\mu }}_{0}I/\left(2R\right)[/latex]. Note that the larger the loop, the smaller the field at its center, because the current is farther away.

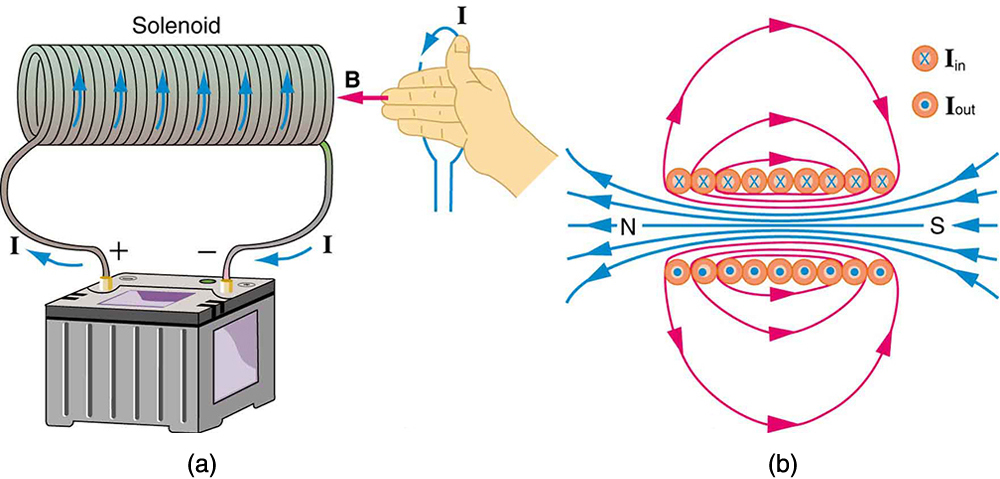

Magnetic Field Produced by a Current-Carrying Solenoid

A solenoid is a long coil of wire (with many turns or loops, as opposed to a flat loop). Because of its shape, the field inside a solenoid can be very uniform, and also very strong. The field just outside the coils is nearly zero. Figure 42.3 shows how the field looks and how its direction is given by RHR-2.

The magnetic field inside of a current-carrying solenoid is very uniform in direction and magnitude. Only near the ends does it begin to weaken and change direction. The field outside has similar complexities to flat loops and bar magnets, but the magnetic field strength inside a solenoid is simply

where [latex]n[/latex] is the number of loops per unit length of the solenoid [latex]n=N/l[/latex], with [latex]N[/latex] being the number of loops and [latex]l[/latex] the length). Note that [latex]B[/latex] is the field strength anywhere in the uniform region of the interior and not just at the center. Large uniform fields spread over a large volume are possible with solenoids, as Example 42.2 implies.

Example 42.2: Calculating Field Strength inside a Solenoid

What is the field inside a 2.00-m-long solenoid that has 2000 loops and carries a 1600-A current?

Strategy

To find the field strength inside a solenoid, we use [latex]B={\mu }_{0}\text{nI}[/latex]. First, we note the number of loops per unit length is

Solution

Substituting known values gives

Discussion

This is a large field strength that could be established over a large-diameter solenoid, such as in medical uses of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The very large current is an indication that the fields of this strength are not easily achieved, however. Such a large current through 1000 loops squeezed into a meter’s length would produce significant heating. Higher currents can be achieved by using superconducting wires, although this is expensive. There is an upper limit to the current, since the superconducting state is disrupted by very large magnetic fields.

There are interesting variations of the flat coil and solenoid. For example, the toroidal coil used to confine the reactive particles in tokamaks is much like a solenoid bent into a circle. The field inside a toroid is very strong but circular. Charged particles travel in circles, following the field lines, and collide with one another, perhaps inducing fusion. But the charged particles do not cross field lines and escape the toroid. A whole range of coil shapes are used to produce all sorts of magnetic field shapes. Adding ferromagnetic materials produces greater field strengths and can have a significant effect on the shape of the field. Ferromagnetic materials tend to trap magnetic fields (the field lines bend into the ferromagnetic material, leaving weaker fields outside it) and are used as shields for devices that are adversely affected by magnetic fields, including the Earth’s magnetic field.

PhET Explorations: Generator

Generate electricity with a bar magnet! Discover the physics behind the phenomena by exploring magnets and how you can use them to make a bulb light.

Section Summary

- The strength of the magnetic field created by current in a long straight wire is given by

[latex]B=\frac{{\mu }_{0}I}{2\mathrm{\pi r}}\left(\text{long straight wire}\right),[/latex]

where [latex]I[/latex] is the current, [latex]r[/latex] is the shortest distance to the wire, and the constant [latex]{\mu }_{0}=4\pi \phantom{\rule{0.15em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.15em}{0ex}}{\text{10}}^{-7}\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}\text{T}\cdot \text{m/A}[/latex] is the permeability of free space.

- The direction of the magnetic field created by a long straight wire is given by right hand rule 2 (RHR-2): Point the thumb of the right hand in the direction of current, and the fingers curl in the direction of the magnetic field loops created by it.

- The magnetic field created by current following any path is the sum (or integral) of the fields due to segments along the path (magnitude and direction as for a straight wire), resulting in a general relationship between current and field known as Ampere’s law.

- The magnetic field strength at the center of a circular loop is given by

[latex]B=\frac{{\mu }_{0}I}{2R}\text{}\left(\text{at center of loop}\right),[/latex]

where [latex]R[/latex] is the radius of the loop. This equation becomes [latex]B={\mu }_{0}\text{nI}/\left(2R\right)[/latex] for a flat coil of [latex]N[/latex] loops. RHR-2 gives the direction of the field about the loop. A long coil is called a solenoid.

- The magnetic field strength inside a solenoid is

[latex]B={\mu }_{0}\text{nI}\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}\left(\text{inside a solenoid}\right),[/latex]

where [latex]n[/latex] is the number of loops per unit length of the solenoid. The field inside is very uniform in magnitude and direction.

Conceptual Questions

Make a drawing and use RHR-2 to find the direction of the magnetic field of a current loop in a motor (such as in Torque on a Current Loop: Motors and Meters Figure 41,1). Then show that the direction of the torque on the loop is the same as produced by like poles repelling and unlike poles attracting.

Glossary

- right hand rule 2 (RHR-2)

- a rule to determine the direction of the magnetic field induced by a current-carrying wire: Point the thumb of the right hand in the direction of current, and the fingers curl in the direction of the magnetic field loops

- magnetic field strength (magnitude) produced by a long straight current-carrying wire

- defined as [latex]B=\frac{{\mu }_{0}I}{2\mathrm{\pi r}}[/latex], where [latex]I[/latex] is the current, [latex]r[/latex] is the shortest distance to the wire, and [latex]{\mu }_{0}[/latex] is the permeability of free space

- permeability of free space

- the measure of the ability of a material, in this case free space, to support a magnetic field; the constant [latex]{\mu }_{0}=4\pi ×{\text{10}}^{-7}\phantom{\rule{0.25em}{0ex}}T\cdot \text{m/A}[/latex]

- magnetic field strength at the center of a circular loop

- defined as [latex]B=\frac{{\mu }_{0}I}{2R}[/latex] where [latex]R[/latex] is the radius of the loop

- solenoid

- a thin wire wound into a coil that produces a magnetic field when an electric current is passed through it

- magnetic field strength inside a solenoid

- defined as [latex]B={\mu }_{0}\text{nI}[/latex] where [latex]n[/latex] is the number of loops per unit length of the solenoid [latex]n=N/l[/latex], with [latex]N[/latex] being the number of loops and [latex]l[/latex] the length)

- Biot-Savart law

- a physical law that describes the magnetic field generated by an electric current in terms of a specific equation

- Ampere’s law

- the physical law that states that the magnetic field around an electric current is proportional to the current; each segment of current produces a magnetic field like that of a long straight wire, and the total field of any shape current is the vector sum of the fields due to each segment

- Maxwell’s equations

- a set of four equations that describe electromagnetic phenomena