34 Gustatory System

Your gustatory system, which mediates your sense of taste, helps you walk the line between health and illness. It acts as a short-range detection system, as you must actually put something in your mouth to taste it.

The gustatory system guides you towards foods that are energy rich and keeps you away from food that could make you sick. Humans can perceive five basic tastes: salty, sour, bitter, sweet, and umami. These specific taste modalities all support this balance. Sweet foods taste good because foods rich in sugar, such as fruit and wheat, contain large amounts of usable energy, and humans have evolved to find these foods appetizing. In contrast, toxic compounds are often bitter, causing you to respond with feelings of disgust. Salty taste indicates a substance with high salt content and sour taste indicates an acidic food, and umami taste indicates a high protein food.

Some of our taste is innate, like sweetness, whereas other tastes are learned like bitterness. This explains why many individuals do not initially like the taste of coffee, and why many individuals prefer to have their coffee with sugar when they first start drinking it. Our tastes can also be modified by our dietary needs, like craving a salty food.

Organs of Taste

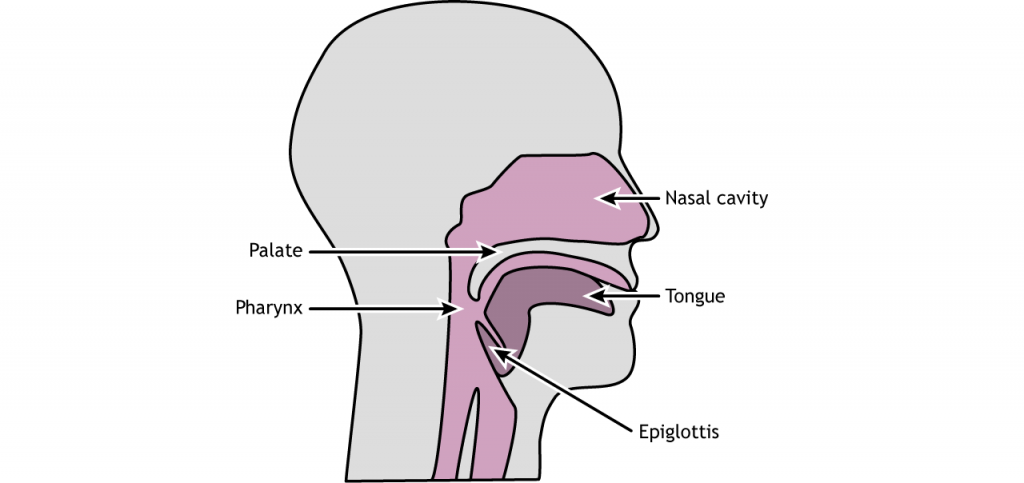

Although taste receptor cells are most prevalent on the tongue, there are other regions of the mouth and throat, including the palate, pharynx, and epiglottis, that also are sensitive to food and play a role in taste perception.

Other sensory information is also tightly linked to our sense of taste. Smell is important in our sense of taste as odorant compounds from food can reach odor receptors in the nasal cavity. How a food looks (sense of vision) is also important to how it tastes. The texture and temperature of the food is also important (somatosensory information). Even a sense of pain, related to the spicy level of the food relates to our sense of taste.

Tongue anatomy

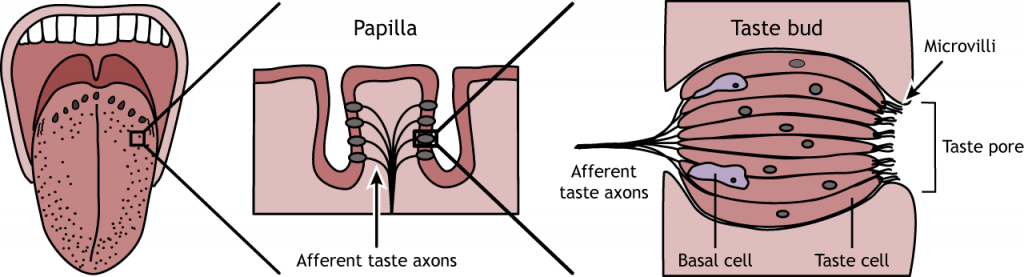

The surface of the tongue is covered in small, visible bumps called papillae. Taste buds are located within the papillae, and each taste bud is made up of taste receptor cells, along with supporting cells and basal cells, which will eventually turn into taste receptors cells.

The taste cells have a lifespan of approximately two weeks, and the basal cells replace dying taste cells. The taste cells have microvilli that open into the taste pore where chemicals from the food can interact with receptors on the taste cells. Although taste cells are not technically neurons, they synapse and release neurotransmitters on afferent axons that send taste perception information to the brain.

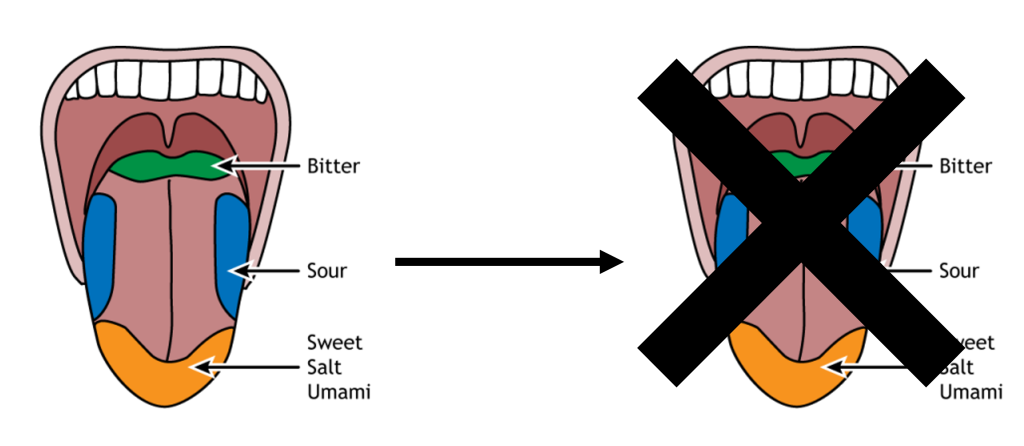

The entire tongue is capable of perceiving all five tastes, meaning there are taste receptors for each taste present across the entire surface. However, some regions of the tongue have a slightly lower threshold to respond to some tastes over others. The tip of the tongue is the region most sensitive to sweet, salt, and umami tastes. The sides are most sensitive to sour, and the back of the tongue to bitter tastes.

Taste transduction

Currently, it is believed that humans sense five basic tastes: Salty, sour, sweet, bitter, and umami. Salty and sour taste are both mediated by ionotropic taste receptors, while sweet, bitter, and umami taste are mediated by metabotropic taste receptors.

Salt

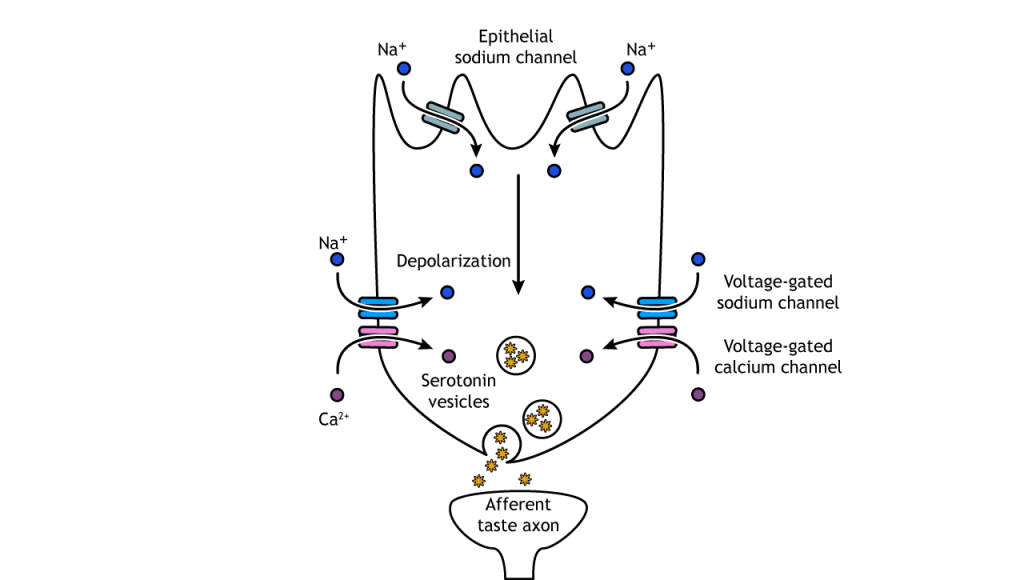

Salt taste is mediated by the presence of epithelial sodium channels. These receptors are usually open, and when foods are ingested with high salt concentrations, sodium flows into the cell causing a depolarization. This change in membrane potential opens voltage-gated sodium and calcium channels. The increased calcium influx causes the release of serotonin-filled vesicles. The serotonin acts on the afferent taste axon causing depolarization and action potentials.

Salty foods elicit a biphasic response depending on concentration. Foods cooked with a low concentration of salt taste bland and are not very appetizing; however, high salt concentrations elicit a strong aversive reaction – imagine how disgusted you were when you first tried to cook and were overly generous with the salt!

Additionally, the appeal of salt at a given moment depends on our body’s need for salt at the time. Several hormones such as the appetite-stimulating hormone ghrelin contribute to regulating the concentration of salt in the body by mediating Na+ absorption. Current salt levels can also impact appetite for salt. For example, in chronically-sodium deprived animals, high salt solutions are highly rewarding.

Why are we so sensitive to the taste of salt? As it turns out, both sodium and chloride are essential nutrients. They are critical for maintaining blood volume and pressure, for regulating body water, for maintaining muscle contractions, and mediating action potentials.

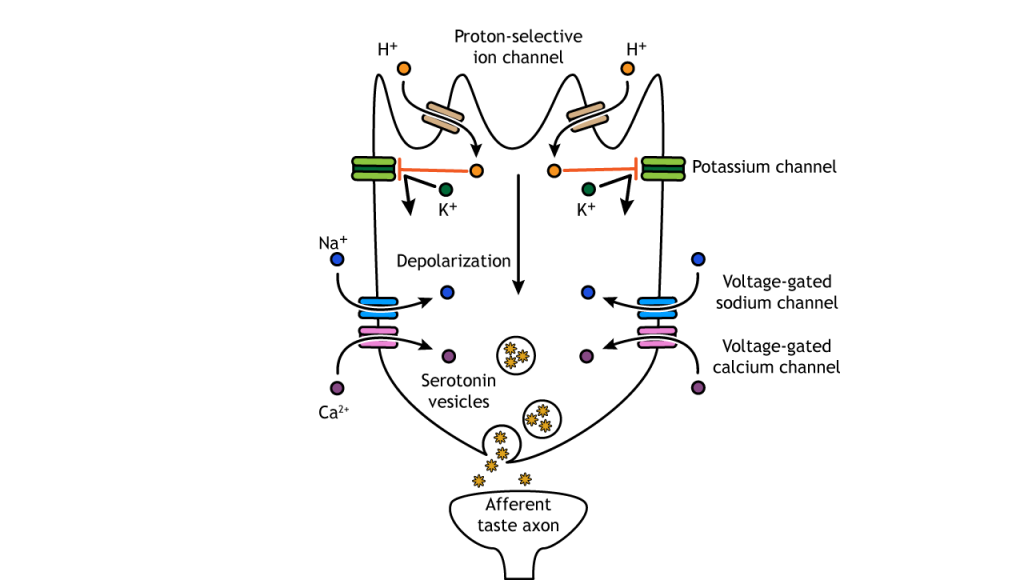

Sour

Foods taste sour because of their acidity, and when acids are present in water, they produce hydrogen ions (protons). Therefore, a sour food has high acidity and a high concentration of hydrogen ions, thus a low pH. The exact mechanism for sour taste transduction has yet to be worked out, but it is believed that protons enter the cell through an ion channel, and then block potassium channels. The decreased efflux of potassium, along with the presence of the protons, depolarizes the cell causing voltage-gated sodium and calcium channels to open. Like salt taste transduction, the increase in intracellular calcium causes release of serotonin into the synapse.

The purpose for our ability to sense acids in our food is under debate. Sour tastants do not inherently provide any nutritional value, except in the case of Vitamin C. Humans and other higher primates cannot synthesize Vitamin C on their own, so it’s possible that we evolved to find a combination of sourness and sweetness attractive enough to consistently consume Vitamin C-rich fruits. However, sour can be aversive, motivating us to avoid spoiled or unripe foods that might contain pathogens.

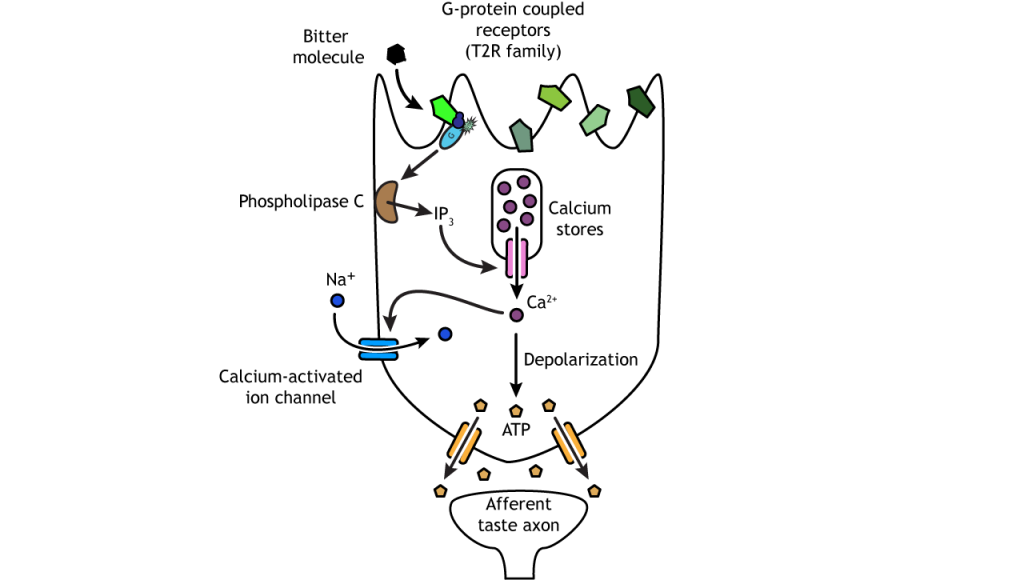

Bitter

Bitter, sweet, and umami compounds all activate taste receptor cells via G-protein coupled receptors. The bitter receptors are from the T2R family of receptor proteins; humans have over 25. Each taste cell can express most or all of the different receptor types, allowing for the detection of numerous molecules, which is important when wanting to avoid dangerous substances like poisons and toxins.

Activation of the G-protein receptor activates phospholipase C, which in turn increases production of the second messenger inositol triphosphate. Inositol triphosphate causes the release of calcium from intracellular stores. Calcium causes the opening of ion channels, allowing the influx of sodium. These ion changes depolarize the cell and cause ATP-specific channels to open, allowing ATP to flow out of the cell and enter the synapse to act on the afferent taste axon by binding to purinergic receptors on the postsynaptic cell.

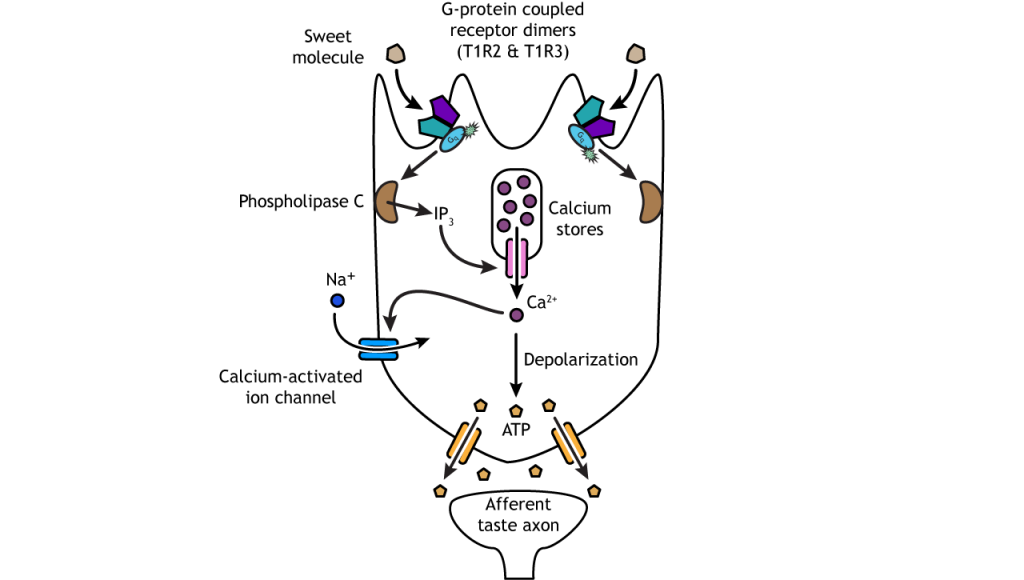

Sweet

Sweet and umami receptors are comprised of G-protein coupled dimers, meaning two separate proteins function together as one. The receptors are encoded by the T1R family of receptor proteins. Sweet receptors are dimers of the T1R2 and T1R3 proteins. Both proteins need to be present and functioning for activation of a sweet taste cell. Like bitter cells, activation of the G-protein receptor uses a second messenger system to release calcium from intracellular stores and increase the influx of sodium. These ion changes depolarize the cell and cause ATP-specific channels to open, allowing ATP to enter the synapse and act on the afferent taste axon.

Sugars like glucose and sucrose are essential for the survival of a species, since they are the main source of cellular energy. Therefore, our ability to detect sweetness plays a central role in regulating how much energy we take into our bodies. Of all the taste modalities, sweet is the strongest driver of food selection.

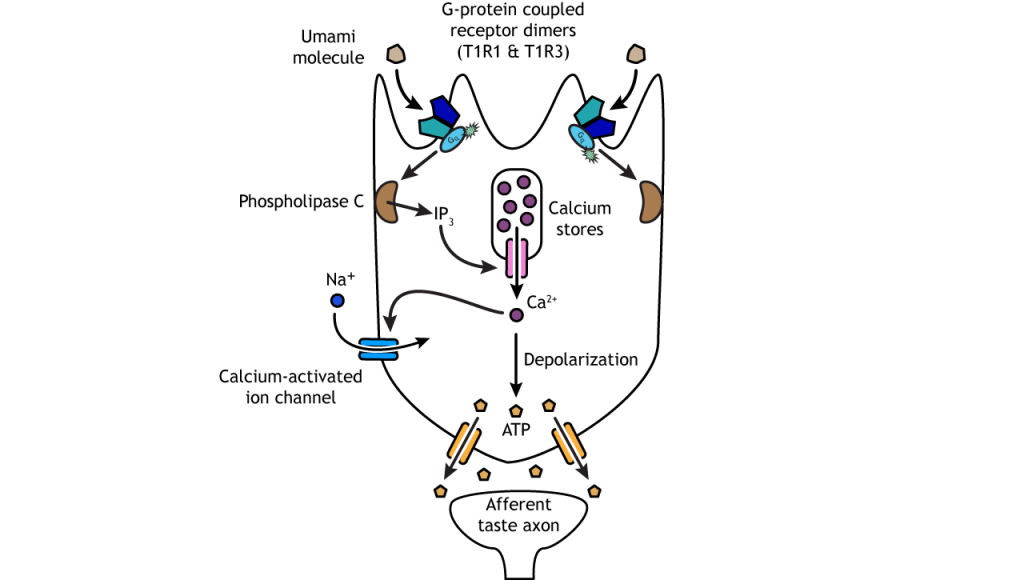

Umami

Umami is the taste of savory deliciousness, such as the taste of rich chicken broth, a perfect medium-rare steak, or aged cheese. The word is derived from the Japanese word umai, which means “delicious.” Umami is signaled when a molecule of glutamate (chemically the same as the neurotransmitter) binds to T1R1/T1R3 receptors.

Umami receptors are comprised of the T1R3 protein, like the sweet receptor, but it is paired with the T1R1 protein. Once the G-protein coupled receptor is activated, the transduction pathway is the same as bitter and sweet taste cells.

Through evolution, we have come to prefer the taste of umami because glutamate is a byproduct of cooking food. Cooking foods changes their chemical properties, thereby improving digestion, reducing toxicity, and increasing absorption of nutrients. Glutamate is one of the byproducts in the process of heating a food, and so it benefits us to appreciate these flavors.

Coding Properties of Taste

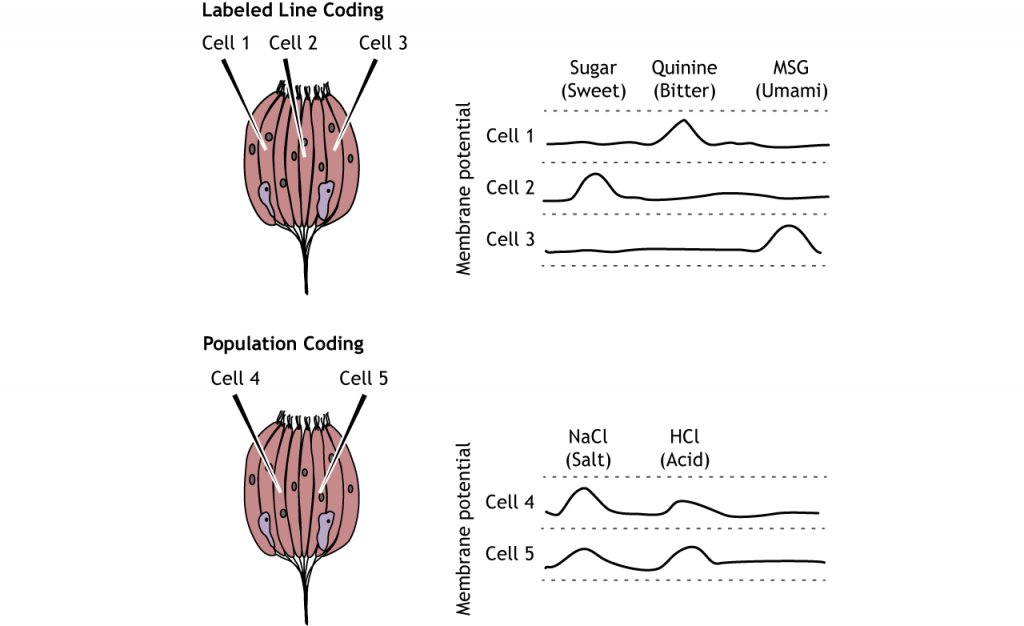

Of the five tastes, only two neurotransmitters are used to communicate information to the central nervous system, so how does our brain know what tastes to perceive? The answer is how the information is encoded. Most taste cells use a labeled line coding method, which means that each cell and the related afferent taste axon only responds to one type of taste. For example, bitter cells only express bitter receptors and are only activated by bitter molecules. These bitter taste cells activate bitter sensory neurons and bitter regions of the taste cortex.

A small portion of taste cells do use population coding as well, meaning more than one tastant can activate the cell, and perception is based on a combination of multiple cells each with a different response. Most information, however, is encoded via labeled line at the level of the taste cell.

Pathway

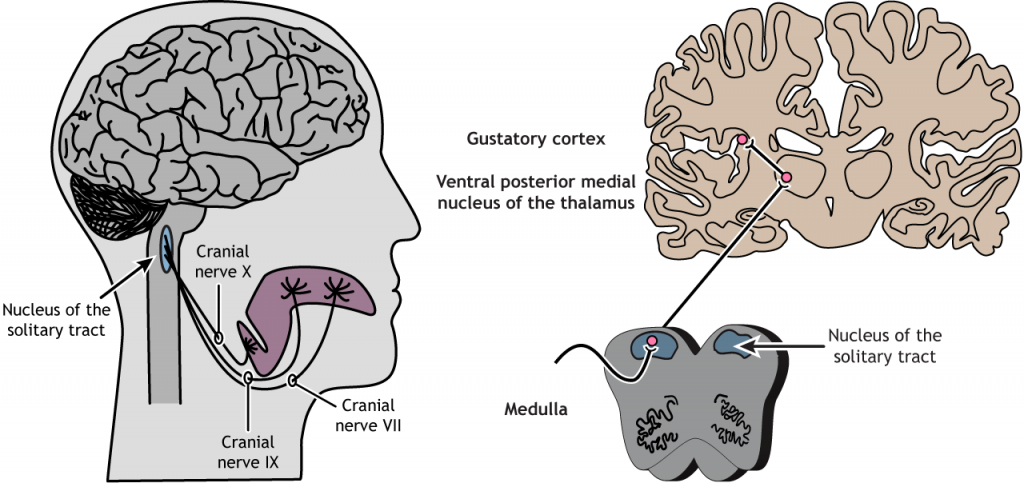

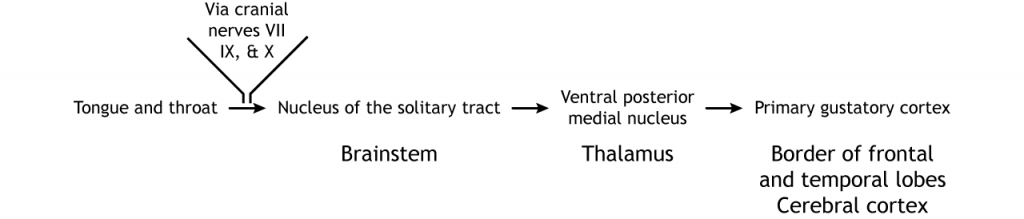

The tongue is innervated by three cranial nerves. The front two-thirds of the tongue is innervated by cranial nerve VII (Facial nerve). The back third is innervated by cranial nerve IX (Glossopharyngeal nerve). Finally, the epiglottis and pharynx are innervated by cranial nerve X (Vagus nerve). All three cranial nerves enter the brainstem at the medulla and synapse in the nucleus of the solitary tract. From there, information is sent to the ventral posterior medial nucleus of the thalamus. Thalamic neurons send projections to the gustatory cortex. The gustatory cortex is located deep in the lateral fissure in a region called the insula. Information processing taste stays primarily on the ipsilateral side of the nervous system that is to say, taste information from the left half of the tongue gets represented in the left hemisphere of the brain, and visa versa.. Projections within the brain also exist between the taste regions and the hypothalamus and amygdala.

View the facial nerve (cranial nerve VII) using the BrainFacts.org 3D Brain

View the glossopharyngeal nerve (cranial nerve IX) using the BrainFacts.org 3D Brain

View the vagus nerve (cranial nerve X) using the BrainFacts.org 3D Brain

View the thalamus using the BrainFacts.org 3D Brain

Flavor

How do 5 basic tastes turn into the myriad complex taste sensations we experience when eating food? Olfaction plays an important role in the perception of flavor, as do vision and touch. Taste information combines with information from these other sensory systems in the orbitofrontal cortex located in the frontal lobe. This region is believed to be important for the pleasant and rewarding aspects of food. Additionally, as taste is processed in higher-order regions of the CNS, information is combined using population coding mechanisms. Test how your senses combine to create flavor at home!

View the orbitofrontal cortex using the BrainFacts.org 3D Brain

Key Takeaways

- Taste cells express specific taste receptors and are located in taste buds within the papillae

- Salt and sour taste cells rely on ion channels to depolarize the cell and release serotonin

- Bitter, sweet, and umami taste cells rely on G-protein coupled receptors and second messengers that open ATP channels

- At the level of the taste receptor cells, taste is perceived by using labeled line coding

- Multiple regions in the mouth and throat play a role in processing of taste

- Three cranial nerves innervate the tongue and throat

- The cranial nerves synapse in the nucleus of the solitary tract in the medulla. Information then travels to the ventral posterior medial nucleus of the thalamus and then to the gustatory cortex

- To perceive complex flavors, information from other sensory systems is combined with taste information in the orbitofrontal cortex

Test Yourself!

Attributions

Portions of this chapter were remixed and revised from the following sources:

- Foundations of Neuroscience by Casey Henley. The original work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

- Open Neuroscience Initiative by Austin Lim. The original work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Media Attributions

- Maps of tastes on the tongue © Casey Henley adapted by Valerie Hedges is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Posterior Parietal © Casey Henley adapted by Valerie Hedges is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license