62 Psychiatric Disorders: Anxiety

Psychiatric Disorders

The brain can be thought of as a well-oiled machine made up of hundreds of billions of moving parts, all cooperating in tandem for healthy behavior and function. There is redundancy in the way these parts are organized, allowing for occasional mishaps without any significant loss of function. But when these parts interact in unusual or atypical ways, a person may develop some psychiatric disorder. The conditions described in the next three chapters likely involve dysregulations in molecules, cells, or circuits, and are therefore complex.

As far as we know, the likelihood of developing these conditions is not exclusively determined by either genes or influence from the environment. Instead, there is probably some influence from both. That is to say, none of these conditions are 100% penetrant; none of them are dictated exclusively by genetics. Having two parents or an identical twin with the condition may indicate an elevated baseline risk over the population at large, but it is not a guarantee that the disease will manifest. Environmental triggers and other exposures may lead to a sudden onset of the condition; on the other hand, certain factors in the environment may be protective against these diseases.

One of the major challenges with understanding these brain diseases is related to the difficulty of making an accurate diagnosis—as almost everything in biology exists on a spectrum, so do these brain disorders. The symptoms of these disorders frequently overlap, adding another layer of complexity. To help establish a diagnosis, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) has put together a series of criteria for psychiatrists to diagnose these complex conditions. Recall our previous discussion of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), used for compiling symptoms and diagnostic criteria.

Many of the treatments we currently have for neuropsychiatric disorders aren’t always effective. Our ability to treat these conditions depends on our understanding of the disease. The better we understand the causes of these conditions, the wider variety of new therapies we can test. Therapeutic strategies for these conditions are often first tested using cells and non-human animal models, but these have shortcomings. Most of the time, animal models of disease incompletely mimic the symptoms of the disease. Unfortunately, we don’t have any animal models that reproduce the symptoms of the most complex human conditions—it is almost impossible to create a mouse model of dissociative identity disorder or dyslexia, and even if we could, scientists would struggle to quantify the behaviors that we use as diagnostic criteria, which are too subtle to be observed or quantified in non-humans. And for the animal models that we do have, they are often imperfect or incomplete, modeling only some of the deficits seen in humans. Furthermore, most human diseases have many symptoms, and only a few can be assessed with behavioral tests. We can only study disorders of the brain that have a clearly and easily quantifiable behavioral component.

Anxiety Disorders

Anxiety is something that everyone has experienced at many points in their life. An anxious person may experience cardiovascular symptoms such as elevation of blood pressure and heart rate, shortness of breath, profuse sweating, and a state of panic. In many ways, the anxiety response is similar to the fight-or-flight response observed during sympathetic nervous system activity. However, a clinical diagnosis of anxiety is different from the passing anxiety that we all experience. Anxiety disorders are characterized by fear, which is an adaptive response to an external threat or stressor.

Common Anxiety Disorders

Anxiety disorders can be very common, and lifetime prevalence estimates suggest 29% of people could develop clinically significant anxiety over their life span.

There are various anxiety disorders. Some are described below.

- Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). People with GAD experience a constant sensation of being overwhelmed, accompanied by fear and worry. Many times, this worry is not about a single concern, but rather a combination of issues all at once, such as financial issues, relationship issues, uncertainty of the future, and many others. GAD is much more severe and persists longer than the normal worries that affect everyone. In GAD, worry persists for several months and is uncontrollable. There are also associated cognitive symptoms, such as fatigue, irritability, difficulty with concentration, and changes in sleep patterns.

- Specific phobias. With specific phobias, a person develops the anxiety-related symptoms (cardiovascular and psychological changes) in response to highly specific stimuli, such as snakes, enclosed spaces, deep ocean, or public speaking. The person with the phobia perceives the stimulus to be a great threat, even though it does not actually pose a genuine threat. Most people with specific phobias will go to great lengths to avoid exposure to their particular phobia trigger. These phobias are often influenced by social and cultural conditions. Developing a specific phobia has a lifetime prevalence of about 7%, but only a very small number of people with specific phobias ever seek treatment for their phobia. Like other forms of anxiety, there is a range of severity of these phobias.

- Panic disorder. A person with panic disorder experiences frequent panic attacks, characterized by sudden increases in heart rate, shortness of breath, dizziness, and sudden numbness or tingling (panic attacks can also be seen in specific phobias, but are not observed in GAD.) In panic disorder, these panic attacks may occur independently of external influences.

- Agoraphobia. Agoraphobia involves a fear of entrapment or of having no escape. Individuals with agoraphobia may avoid crowds of people, riding elevators or cars, and crossing bridges.

- Social phobia. Social phobia is similar to more specific phobias, however, with social phobia there is a specific fear of public speaking or being in social situations.

- Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). OCD is a common psychiatric condition affecting an estimated 3% of the population, characterized by persistent intrusive thoughts or the need to perform some ritualistic series of actions or motions. OCD exists on a spectrum, and in severe cases, can severely impair the quality of an individual’s life.

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Anyone can be diagnosed with PTSD at any point in their lives. Some of the most common events that lead to a PTSD diagnosis include combat experience, physical, emotional, or sexual assault or abuse, accidents, and natural disasters. Women are twice as likely as men to be diagnosed with PTSD. Genetic influence appears to account for approximately 30-40% of risk. The symptoms of PTSD are usually divided into three categories: Re-experiencing, Avoidance, Hyper-arousal. Re-experiencing symptoms arise when stimuli cause PTSD patients to relive their traumatic experience in flashbacks, frightening thoughts, or nightmares. Avoidance symptoms arise when PTSD patients feel lack of emotion, lose interest in activities they once enjoyed, or withdraw from family and friends. These symptoms may be a result of trying to avoid reminders or triggers of the traumatic event. Hyper-arousal symptoms appear as increased anxiety or feeling tense in safe environments. PTSD patients can be easily frightened, may have trouble sleeping, and may have frequent angry outbursts.

Theories of Anxiety Disorders

The exact cause of anxiety is still unknown. One theory suggests that anxiety is a maladaptive evolutionary response to our modern living conditions. The argument is based on the observation that an anxiety response looks a lot like a mild version of the fight-or-flight, sympathetic nervous system response: both elicit cardiovascular and respiratory changes.

For the majority of the evolutionary history of Homo sapiens, we benefited from the sympathetic nervous system as a reflex to improve the odds of survival in dangerous situations. However, our modern civilized living conditions over the past few centuries have been very tame in comparison to the risks that our earlier ancestors experienced. The relative ease of living has let the main function of the sympathetic nervous system fall into disuse. The theory argues that people experience GAD because a part of them encourages sustained activity in the sympathetic nervous system. Although thought-provoking, this theory can’t be tested experimentally and offers no explanation about a biological mechanism that can help to develop a therapy.

Treatments for Anxiety Disorders

There are various treatments for anxiety disorders.

- Psychotherapy utilizes a therapist that performs exposure therapy for the individual to practice being put in a situation that would normally cause anxiety and a fearful response to learn that the situation is not actually dangerous. This treatment has been demonstrated to be very effective but does take time and can be uncomfortable for the individual receiving the therapy.

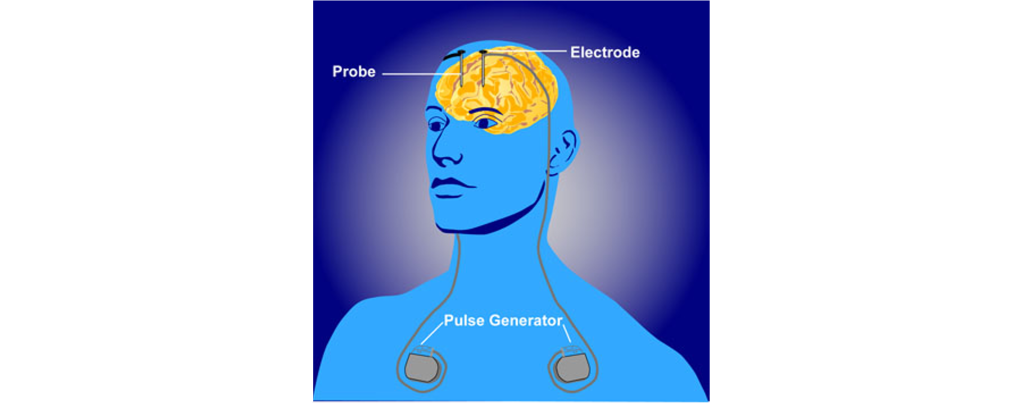

- Deep brain stimulation is a medical intervention in which a surgeon implants permanently indwelling electrodes directly into brain tissue. These electrodes are controlled by an external battery pack that delivers preprogrammed stimulation protocols. Deep brain stimulation has been approved for treating obsessive compulsive disorder and is being tested as a potential treatment for a number of other disorders.

Figure 62.1. Deep brain stimulation. A deep brain stimulator device must be implanted surgically. Electrodes are positioned in specific brain areas for the delivery of electrical impulses. The impulses come from an external battery pack that is typically implanted beneath the skin on the chest. Deep brain stimulation can be used to treat disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, obsessive compulsive disorder, and depression. - Psychosurgery involves an operation that uses a stereotaxic frame to make very precise alterations to the brain by cutting connections between brain areas or by selectively lesioning brain areas with the goal of correcting abnormal activity within the brain. Psychosurgery is still performed today, but not very often.

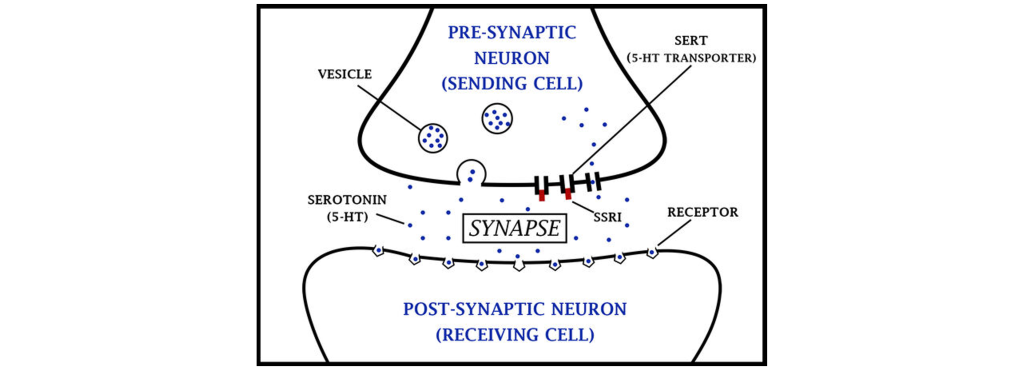

- Anxiolytic Drugs. Pharmacologically, there are a wide variety of drugs that can be used to treat anxiety, broadly called anxiolytics. The first-line therapies are usually selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), the same class of compounds that are used in depression treatment. Other anxiolytics, such as the benzodiazepines alprazolam or clonazepam, act as positive allosteric modulators which increases the effect of the GABA system. Benzodiazepines are not always preferred since they may have abuse potential and can be addictive. Opioids and norepinephrine inhibitors can also decrease anxiety.

Figure 62.2. Action of SSRIs. Serotonin is released from synaptic vesicles within the presynaptic cell and can then cross the synapse and bind to receptors on the postsynaptic cell. The serotonin transporter (SERT) is located on the presynaptic cell membrane. SSRIs (red) block the SERT, causing serotonin concentration within the synapse to increase, which in turn increases the possibility of serotonin binding to postsynaptic receptors.

When treating individuals for anxiety using drugs, the placebo effect is especially strong in those with anxiety disorders. A placebo is an inactive substance that is not made to serve as a treatment, such as a sugar pill. The placebo effect is a real response (can be either negative or positive) that an individual has to receiving a placebo. Interestingly, the mechanisms underlying how the placebo effect works is still largely unknown, but is believed to be related to the mind-body relationship.

SSRIs are the most common treatment for anxiety disorders. A SSRI inhibits reuptake of serotonin by blocking the serotonin transporter (SERT) located on the presynaptic cell, effectively increasing serotonin concentration within the synapse, and increasing the likelihood that serotonin will bind to postsynaptic serotonin receptors. If increasing serotonin at the synapse is an effective treatment for anxiety disorders, to many it logically follows that anxiety disorders are caused by decreased serotonin levels. However, the cause of anxiety disorders is not so clear cut. It is possible that SSRIs might be treating symptoms of the disorders rather than the actual underlying disorder. Alternatively, these drugs may be producing compensatory changes within the brain that ultimately cause them to be effective.

Animal Models to Study Anxiety

There are nonhuman behavioral tests used to assess anxiety in rodents, such as the elevated plus maze. This maze is a raised platform, with four arms in the shape of a plus sign. Two of the arms have walls surrounding the sides, while the other two are open, exposed on all sides. The rodent is free to move between any of the arms as they choose. Standing in one of the open arms, where they can see the floor far below them, is an anxiety-provoking condition. Under normal circumstances, rodents choose to spend more time in the arms that are surrounded by walls. But if you give these animals an anti-anxiety drug, they increase the time spent in the open arms, indicating a decrease in the behavioral expression of anxiety.

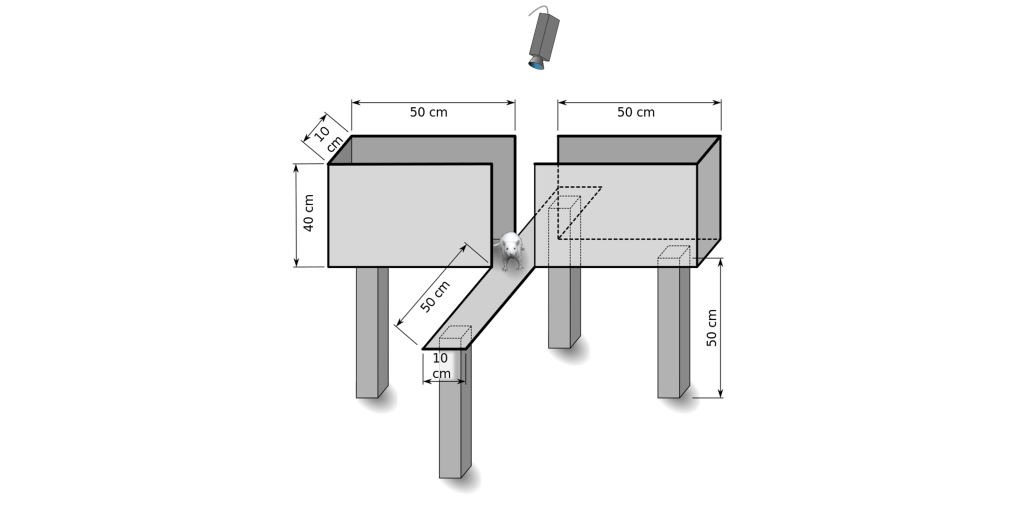

A related behavioral test is the open field test. The test apparatus consists of a large, flat area where the rodent can move around freely, and some method to track the animal—either an aerial view camera or a series of parallel invisible infrared beams that can locate the animal in the field. In the wild, rodents, as prey animals, prefer to spend more time close to the sides of the testing arena up against the wall, avoiding the wide-open space in the middle where their instinct warns them that they may be snatched up by some predator. However, if you give the rodent an anti-anxiety drug, they will spend more time venturing into the middle of the open field.

Another non-human model of anxiety is the predator exposure paradigm. In this paradigm, an ethologically-relevant stimulus is presented to the rodent, such as one of their naturally occurring predators. In this paradigm, rodent anxiety presents itself as a freezing response, an autonomic nervous system activity spike, and a reduction in non-survival behaviors. Although the predator exposure paradigm has good predictive validity, they may struggle with poor face validity, since the anxiety measures also may appear as many of several other conditions, such as PTSD or stress.

Key Takeaways

- Psychiatric disorders are diagnosed through the DSM-5.

- An anxiety response is similar to sympathetic nervous system activity. Anxiety disorder differ from passing anxiety due to an atypical expression of fear to an environmental stressor.

- There are several different anxiety disorders that are all characterized by increased fear.

- The cause of anxiety is largely unknown.

- Treatments for anxiety disorders include psychotherapy, deep brain stimulation, psychosurgery, and anxiolytic drugs.

- Animal models are used to study anxiety, though they are not capable of completing mimicking the symptoms of complex psychiatric disorders.

Attributions

Portions of this chapter were remixed and revised from the following sources:

- Open Neuroscience Initiative by Austin Lim. The original work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Media Attributions

- Deep brain stimulation © NIMH adapted by Valerie Hedges is licensed under a Public Domain license

- SSRIs © U3190069 adapted by Valerie Hedges is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- elevated plus maze © Samueljohn.de adapted by Valerie Hedges is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

'Fight or Flight' system

biologically inactive substance that is not meant to serve a therapeutic purpose