63 Psychiatric Disorders: Affective Disorders—Major Depression Disorder

Affective Disorders

Affective disorders are highly prevalent. Affect indicates mood, or emotional state. Therefore, affective disorders are disorders of mood. We will cover two major mood disorders: major depression and bipolar disorder.

Major Depressive Disorder

Episodes of depression can occur throughout an individual’s life with or without an external cause and can last on the order of months or years. Depression is a highly prevalent condition with a lifetime risk of about 18%. Depression gets diagnosed more frequently in women than in men, affecting about 5% of women and 2.5% of men. Even with treatment, there is a high rate of relapse: an estimated 80% of people with depression have more than one episode in their lifetime. The prevalence of depression is similar across both high-income and low-income countries, indicating that biological factors contribute significantly to the disease. Major Depression Disorder is also called unipolar depression to differentiate it from the depression that represents a phase seen in bipolar disorder.

Clinical depression is often associated with another medical or psychiatric condition. For example, rates of depression are higher among people with terminal diagnoses, like cancer. In this case, we say that the two are comorbid. Additionally, a set of particularly challenging circumstances, like the death of a loved one, could trigger a depressive episode. Major Depression Disorder represents a severe health risk across all ages. About 18% of adolescents report at least one instance of non-suicidal self-injury, and the lifetime risk for suicide among people with Major Depression Disorder is estimated to be about 10%.

Symptoms of Major Depression Disorder

The fundamental criteria that are used to diagnose people with Major Depression Disorder is a depressed mood/self-esteem, low energy, and anhedonia, the decrease in sensitivity to pleasure. Because of the decrease in pleasure, they have a lessened desire to engage in activities that once produced happiness, thus leading them to become withdrawn from their friends and family. Short-term changes in mood are completely normal and not clinical. The main diagnostic criteria for Major Depression Disorder is the severity and duration of the symptoms. When the depression begins to affect other aspects of life, including feelings of worthlessness, changes in sleep or appetite, difficulty concentrating, or suicidal ideation that persist daily for two weeks or longer, then a person may be diagnosed as clinically depressed.

To diagnose Major Depression Disorder, a trained psychiatrist or psychologist would use a combination of interview with a self-report questionnaire such as the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D scale) or the Beck Depression Index. Items that appear on these sorts of tests include: “Feels like life is not worth living”, “Experience frequent weeping”, “I blame myself all the time for my faults”, etc. To date, there is no biomarker for depression.

Biological Basis of Affective Disorders

Monoamine Hypothesis

The monoamine hypothesis of affective disorders postulates that there is decreased signaling within monoamine neurotransmitter systems and is based on observations in depressed patients. First, treatment with different pharmacological substances has indicated that the monoamines serotonin and/or norepinephrine are involved in affective disorders. The drug reserpine blocks the vesicular monoamine transporter that is responsible for the loading of monoamine neurotransmitters into vesicles prior to release at the synapse and causes severe depression in approximately 20% of people. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors, drugs that inhibit the degradation of monoamine neurotransmitters (therefore increasing monoamine availability) have been demonstrated to improve mood. Lastly, the drug imipramine that blocks both the serotonin transporter and norepinephrine transporter is effective at relieving depression. These pieces of evidence support that affective disorders are a consequence of decreased serotonin and/or norepinephrine signaling.

Serotonin

Serotonin, specifically, has been a neurotransmitter of focus in depression since the 1950’s due to a number of observations in depressed patients. There are lower levels of serotonin metabolites, such as 5-H1AA in the cerebrospinal fluid and diets that are low in tryptophan (the precursor for serotonin synthesis) can cause a return of depressive symptoms. Lastly, a number of drugs that are effective at treating affective disorders act to increase serotonin signaling and/or availability. However, it is important to note that there is also evidence that opposes the theory that affective disorders are due to a deficit in serotonin signaling. Primarily, that the level of serotonin in the synapse is less important than how serotonin acts in the synapse. Plastic changes at the synapse, either presynaptically (altering serotonin synthesis) or postsynaptically (altering expression and sensitivity of serotonin receptors) affect how serotonin or serotonergic drugs act on the synapse.

Norepinephrine

There is also pharmacological data that supports a specific role for norepinephrine in affective disorders. The drug desipramine specifically blocks the reuptake of norepinephrine at adrenergic synapses and has been demonstrated to be effective at treating depression in some individuals. Recall that norepinephrine and serotonin have different synthesis mechanisms, with serotonin synthesized from tryptophan and norepinephrine synthesized from tyrosine. The drug AMPT inhibits the activity of tyrosine hydroxylase, the rate-limiting step of norepinephrine synthesis. For individuals that are successfully treated for depression with the adrenergic drug desipramine, the administration of AMPT results in worsening of depressive symptoms. However, when AMPT is administered to those on serotonergic drugs, it has no effect on depressive symptoms. This evidence indicates that there may be separate groups of individuals in which either serotonin or norepinephrine is the major neurotransmitter system affected in depression.

Diathesis-Stress Hypothesis

Diathesis is a predisposition for a disease. The diathesis-stress hypothesis of affective disorders is based on the observation that mood disorders have a tendency to be more common in families with common genetics. This leads to some individuals having a genetic predisposition for the development of mood disorders. Further, abuse and stress have both been demonstrated to be significant risk factors for the development of mood disorders and anxiety and depression are often comorbid. In the diathesis-stress hypothesis, the HPA axis (discussed in Chapter 61) is where both genetic and environmental factors converge to ultimately cause mood disorders. Specifically, the HPA axis has been shown to be hyperactive in depressed individuals, with increased levels of corticotropin releasing factor (CRF), adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), and cortisol and an overall decrease in negative feedback control of the HPA axis.

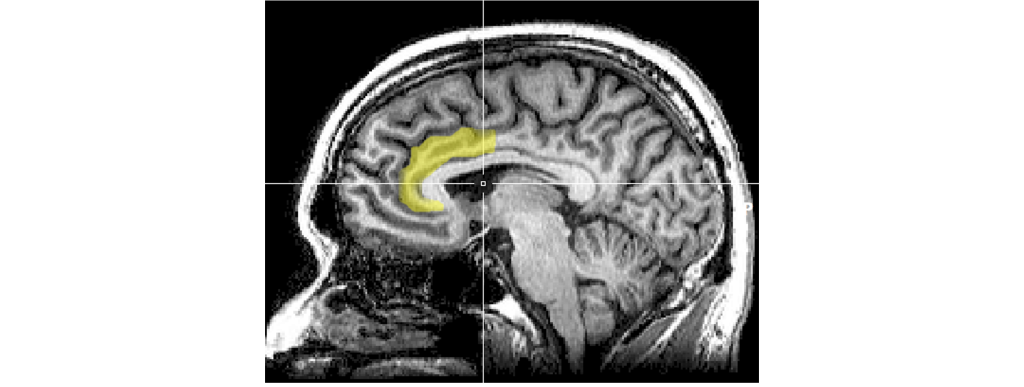

Anterior Cingulate Cortex Dysfunction

The anterior cingulate cortex is a structure that is the anterior most portion of the cingulate cortex just dorsal to the corpus callosum. It is part of the limbic system and typically functions in emotions and in maintaining attention in healthy individuals. Interestingly, the anterior cingulate cortex is interconnected with the HPA axis, the amygdala, prefrontal cortex, and hippocampus. When individuals are sad or depressed there is increased activity within the anterior cingulate cortex, and successful treatment of depression results in decreased activity of the anterior cingulate cortex. It is hypothesized that dysfunction within the anterior cingulate cortex to prefrontal cortex circuit underlies difficulty in concentrating on tasks during depressive bouts.

Treatments for Major Depression Disorder

There is currently no completely effective treatment for Major Depression Disorder that reliably works for everyone. The currently accepted strategies can be divided into behavioral treatments and chemical treatments.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a therapist-guided form of talk therapy that may help a person manage their depression. In CBT, a patient’s behavior, including their coping mechanisms, erroneous thoughts, and emotional responses, is analyzed through careful clinical examination and patient self-reflection. Then, the patient is taught mechanisms to counteract those maladaptive behaviors and replace them with adaptive behaviors. For example, a person undergoing CBT for Major Depressions Disorder might learn to identify the moments when they dwell on something negative in their lives, and then learn to tell themselves: “That thought does not function to make my day better. Let’s start the day by getting out of bed and see what happens next.” It should be known that CBT is not exclusively for the treatment of Major Depression Disorder; CBT can also be effective for anxiety, OCD, PTSD, insomnia, substance use disorders, behavioral addictions, and many others.

Pharmacological Treatments

A wide variety of drugs are used for the treatment of depression. The first-generation antidepressants were developed in the 1950s and 1960s. These drugs acted to increase the action of the monoamine neurotransmitters: primarily dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin. Our body uses an enzyme called monoamine oxidase (MAO) which degrades these chemicals into inactive components that do not signal at receptors. These first generation antidepressants block the action of MAO; biochemically, we call them monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs).

In the presence of an MAOI, the neurotransmitter signal remains in the synapse longer, similar to how an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor increases acetylcholine signaling. Most of the MAOIs, while sometimes effective, have fallen out of fashion clinically because of the adverse side effects associated with their biochemical activity. Some of them interact dangerously with foods rich in tyramine (particularly fermented foods, such as aged cheeses or beer, as well as beans and processed meats), an amino acid that is degraded by MAO. Excess tyramine can activate the sympathetic nervous system, and body levels of tyramine can rise to dangerous levels in the presence of an MAOI, leading to adverse cardiovascular events like stroke. Many of the common MAOIs, like phenelzine and isocarboxazid, can be damaging to the liver. Some MAOIs also produce unwanted side effects, such as psychosis or nausea.

A different class of antidepressant drugs called the tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), named for the shape of their chemical structure, was also developed around this time. They generally act as monoamine reuptake inhibitors, resulting in elevated neurotransmitter signaling. Unfortunately, these tricyclics may produce many severe side effects, such as seizures, tachycardia, and heart attacks, so prescriptions must be monitored closely. The tricyclics are still prescribed today for several other nervous system disorders, ranging from insomnia to neuropathic pain, but due to their potential cardiotoxicity, they are not often the first line of treatment in depression.

Our current, most often prescribed class of compounds for Major Depression Disorder, called the third-generation antidepressants, are focused on boosting the signaling activity of serotonin. Instead of preventing degradation, like the MAOIs, these compounds block the reuptake of serotonin out of the synapse. These chemicals are called selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), of which fluoxetine (Prozac) is one of the most well-known examples. While SSRIs can be effective at reversing the side effects of depression, they are not perfect drugs. One shortcoming is that a person needs to be on the drug for 2-4 weeks before they start to experience a clinically meaningful reversal of depressive symptoms. This finding is highly unusual since the pharmacological, molecular-level effects of SSRIs take place within hours after taking the medication.

Similar to SSRIs, SNRIs (serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors) can also be used to treat depression. One of the unsavory side effects of SSRIs is serotonin syndrome, a set of somatic changes resulting from excessive serotonergic signaling. In mild cases, a person may have an elevated body temperature, excessive sweating, rapid heart rate, and elevated blood pressure. In more severe cases, a patient may have severe fevers or seizures. Serotonin syndrome can happen in the event of an SSRI overdose, or as a consequence of some interaction between an SSRI and other drugs like MAOIs, MDMA (ecstasy), amphetamines, or cocaine.

Our newest treatment options for depression, recently approved by the FDA in March of 2019, is esketamine, a dissociative anesthetic typically used as a veterinary tranquilizer and a recreational club drug. Branded as Spravato, it can be administered rapidly via nasal spray. The strength of esketamine is the speed of its action. After taking a dose, the antidepressant effects of the substance can be observed within hours. The speed at which this drug takes effect, makes it ideal for treating severe cases of suicidal thoughts.

One future therapy that is currently making significant medical advancements in curing depression is the use of psychedelic drugs, particularly psilocybin—a substance found in some species of wild mushrooms. As a potent serotonergic agonist, a single dose of psilocybin has been shown to decrease depression scores in various self-report studies with little to no adverse side effects.

Electroconvulsive Therapy

For severe or treatment-resistant depression, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is a treatment option. Introduced in 1938, the procedure has since been refined over the years (it is currently performed under anesthesia) and is considered to be well-tolerated and highly effective. During the procedure, electrodes are placed on the head and electrical current is passed through the electrodes. The mechanism of action that accounts for the therapeutic effects of electroconvulsive therapy are not well-known. Side effects include aches, nausea, and memory loss.

Deep Brain Stimulation

Deep brain stimulation that targets the cingulate cortex or the prefrontal cortex that may be overactive in depression, is ultimately aimed at decreasing activity. This treatment is only pursued when other less invasive treatments are unsuccessful.

Animal Behavioral Tests of Depression

Behavioral neuroscientists have developed a variety of tests to assess the effectiveness of antidepressant drugs in non-humans. They are roughly divided into two categories: despair-based tests and reward-based tests.

Despair-Based Tests

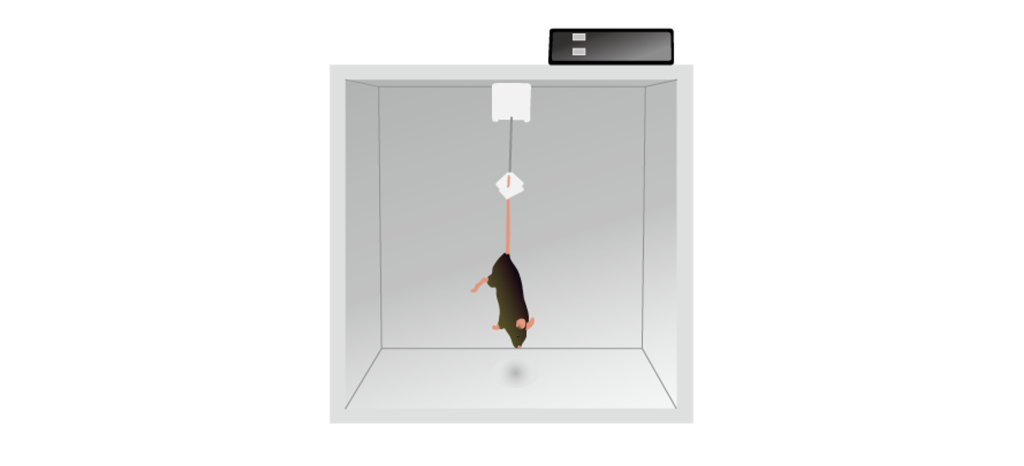

One symptom of depression is that a person “gives up”, a behavior that can be modeled in a variety of rodent tests. One such example is in a tail suspension test. In this test, a rodent is held by the tail upside down. While it does not cause injury to the animal, they do experience discomfort, and will generally struggle to either free themselves or to get upright again. The sooner they stop struggling (more time spent immobile), the more despair they experience, or the more depressive they are. Giving a rodent an antidepressant like fluoxetine causes them to fight for a longer duration.

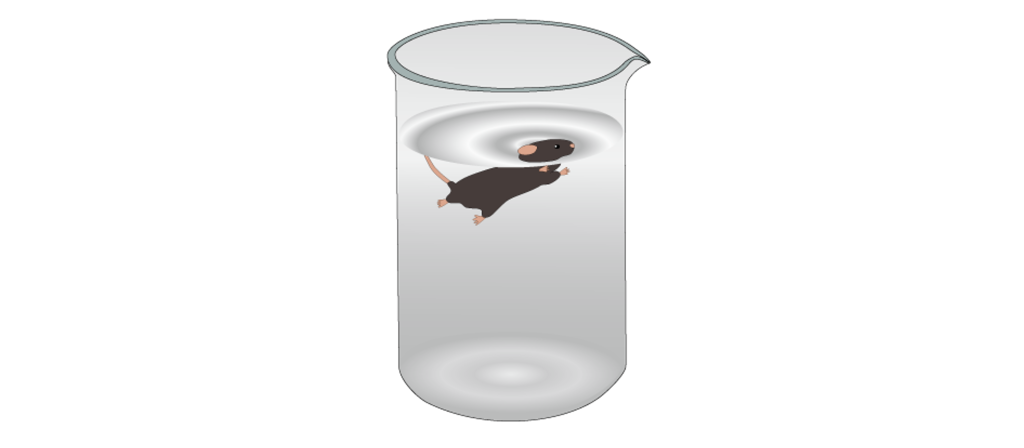

A similar test to assess “giving up” is the forced swim test. Here, a rodent is put into a container with some water. While they are naturally buoyant and are not at risk of drowning, they do not like being wet and will try to swim so that they can climb out of the water-filled container. As in the tail suspension test, they are unable to escape their predicament, and will eventually become immobile. Giving them an antidepressant decreases time spent immobile.

Reward-Based Tests

These tests seek to measure the severity of anhedonia, one of the main symptoms of depression. For example, a rodent may be presented with a two-bottle choice task, where they are put into a cage with two different bottles to drink from: one filled with standard water, and the other filled with a more desirable sugar-water solution. A depressed rodent will not drink from the sugar-water bottle as frequently as a healthy rat but give that rat an antidepressant, and they will prefer the sweet water. An intracranial self-stimulation paradigm can also be tested here in the context of depression. When an electrical stimulator is placed in a reward area of the brain and the rodent is trained to perform some operant task to receive activation of these areas, we find that depressed rodents do not activate these areas of their brain as much as rodents on antidepressants.

Key Takeaways

- Affective disorders are disorders of mood and include Major Depression Disorder and Bipolar Disorder.

- Symptoms of depression include a depressed mood/self-esteem, low energy, and anhedonia.

- Monoamine neurotransmitter systems, especially serotonin and norepinephrine, have been implicated in depression. With decreased signaling in either serotonin or norepinephrine signaling underlies the monoamine hypothesis of depression.

- Hyperactivity of the HPA axis has been observed in depression and underlies the diathesis-stress model of depression.

- Hyperactivity in the anterior cingulate cortex has been observed in depression.

- Treatments for depression include pharmacological treatments, cognitive behavioral therapy, electroconvulsive therapy, and deep brain stimulation.

- Depression is modeled in rodents through tests of despair and tests of reward.

Attributions

Portions of this chapter were remixed and revised from the following sources:

- Open Neuroscience Initiative by Austin Lim. The original work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Media Attributions

- Anterior cingulate cortex © Geoff B Hall adapted by Valerie Hedges is licensed under a Public Domain license

- electroconvulsive therapy © BruceBlaus adapted by Valerie Hedges is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Tail suspension test © DataBase Center for Life Science (DBCLS) adapted by Valerie Hedges is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- forced swim test © DataBase Center for Life Science (DBCLS) adapted by Valerie Hedges is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

mood, or emotional state

refers to when two medical conditions present together

loss of pleasure

predisposition for a disease

therapist-guided form of talk therapy

elevated heart rate