3 Membrane Potential

Casey Henley

The membrane potential is the difference in electrical charge between the inside and outside of a neuron, forming the basis for neural activity. Changes in membrane potential, such as depolarization and hyperpolarization, are key to understanding how neurons function.

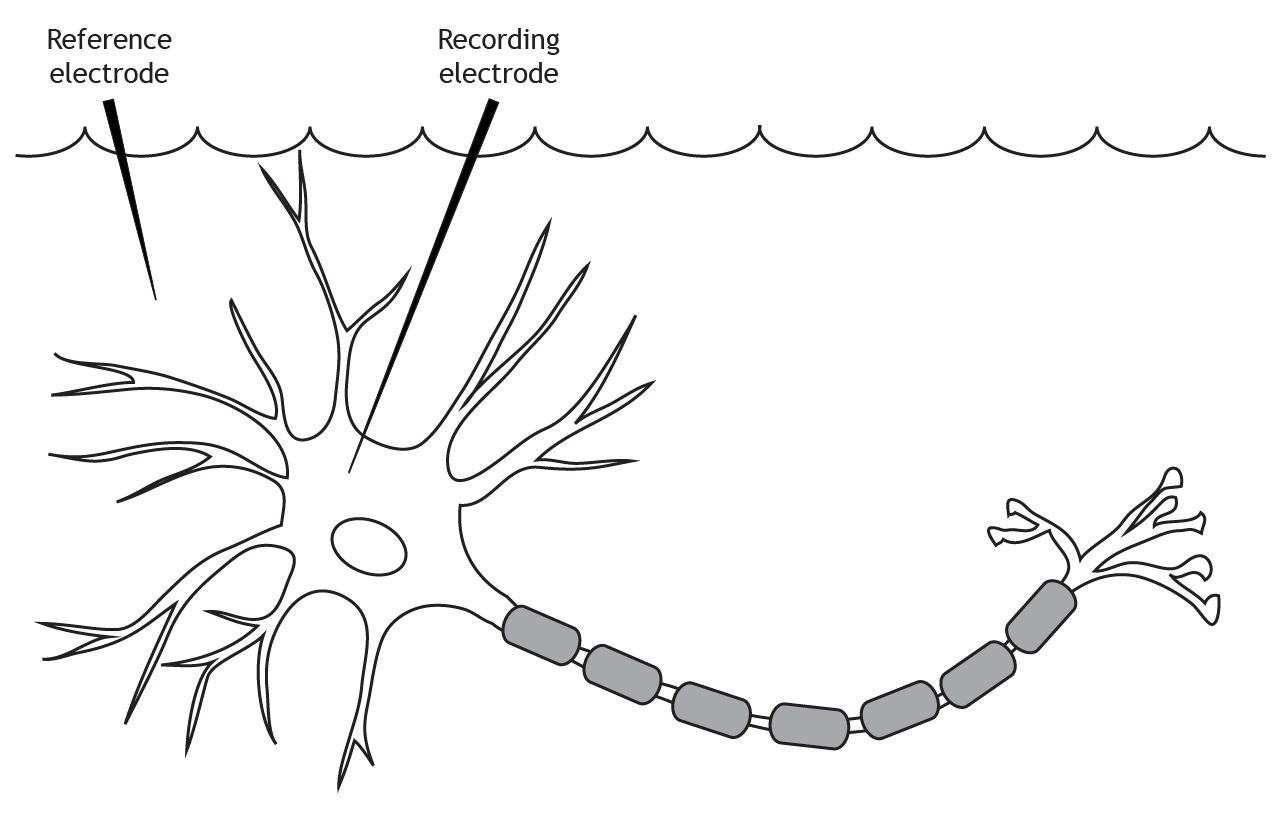

The Membrane Potential

The membrane potential is measured using two electrodes. A reference electrode is placed in the extracellular solution. The recording electrode is inserted into the cell body of the neuron.

Terminology

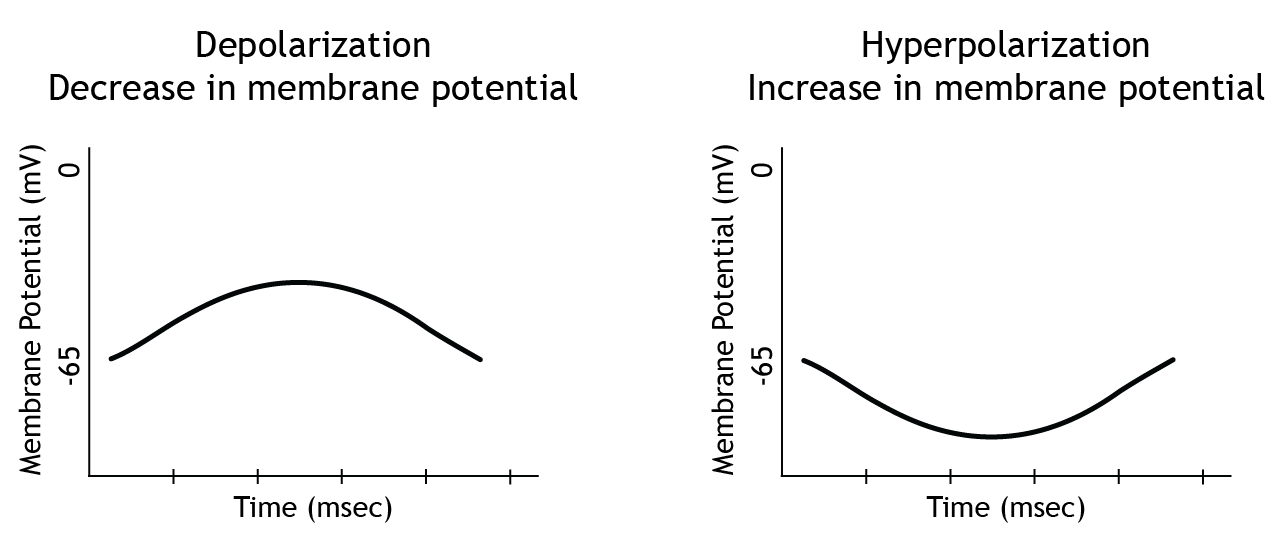

There is more than one way to describe a change in membrane potential. If the membrane potential moves toward zero, that is a depolarization because the membrane is becoming less polarized, meaning there is a smaller difference between the charge on the inside of the cell compared to the outside. This is also referred to as a decrease in membrane potential. This means that when a neuron's membrane potential moves from rest, which is typically around -65 mV, toward 0 mV and becomes more positive, this is a decrease in membrane potential. Since the membrane potential is the difference in electrical charge between the inside and outside of the cell, that difference decreases as the cell's membrane potential moves toward 0 mV.

If the membrane potential moves away from zero, that is a hyperpolarization because the membrane is becoming more polarized. This is also referred to as an increase in membrane potential.

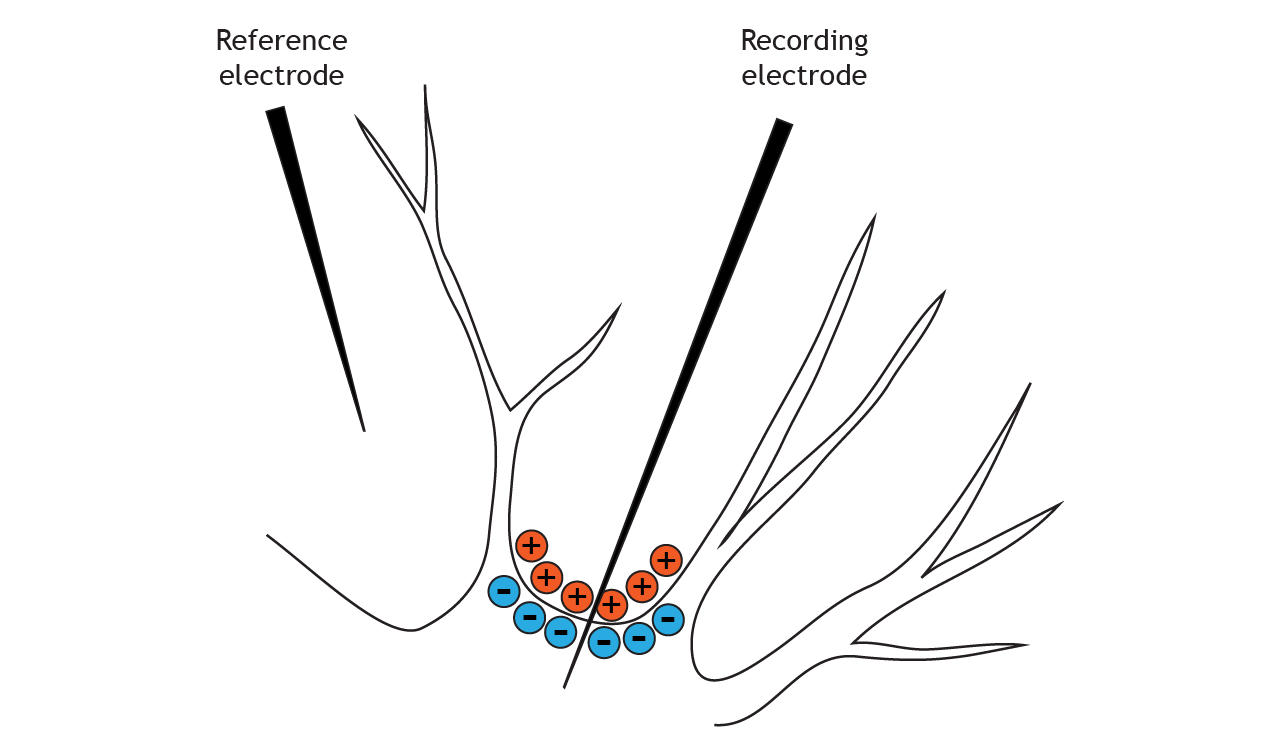

The solution inside of the neuron is more negatively charged than the solution outside

Voltage Distribution

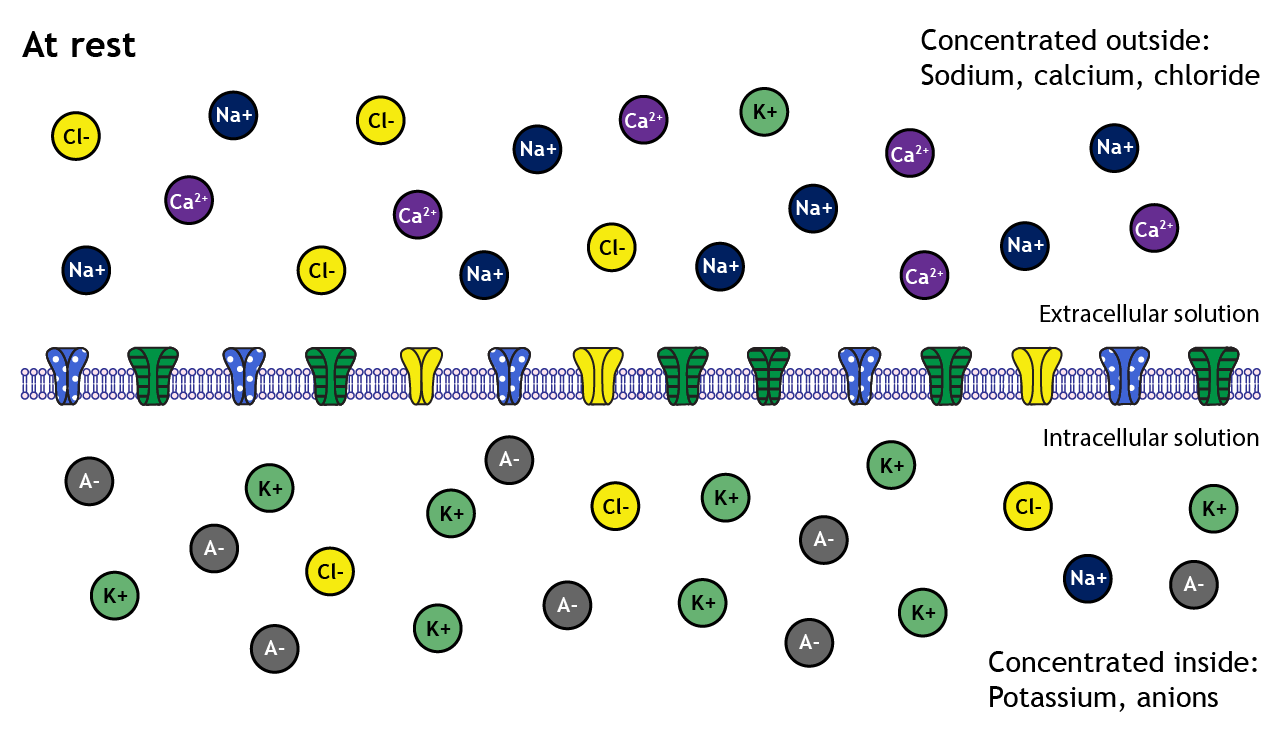

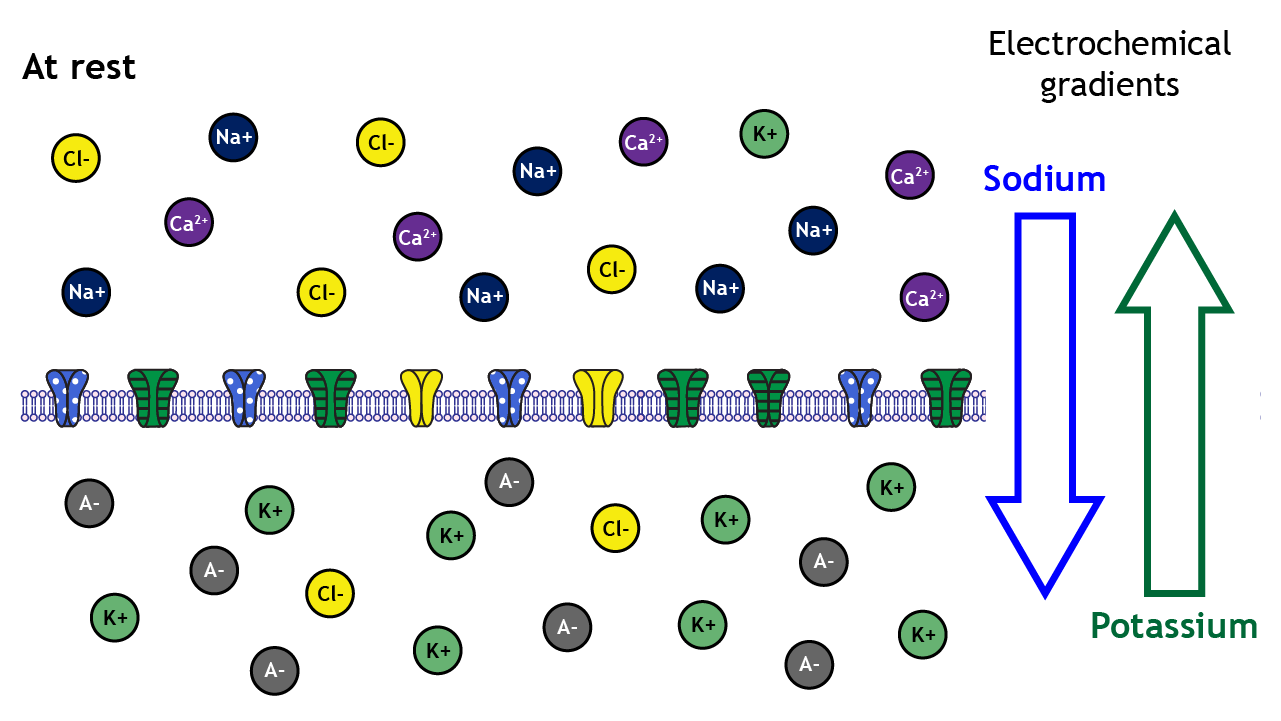

At rest, ions are not equally distributed across the membrane. This distribution of ions and other charged molecules leads to the inside of the cell having a more negative charge compared to the outside of the cell.

A closer look shows that sodium, calcium, and chloride are concentrated outside of the cell membrane in the extracellular solution, whereas potassium and negatively-charged molecules like amino acids and proteins are concentrated inside in the intracellular solution.

The distribution of the different ions across the membrane creates electrochemical gradients that drive ion movement

These concentration differences lead to varying degrees of electrochemical gradients in different directions depending on the ion in question. For example, the electrochemical gradients will drive potassium out of the cell but will drive sodium into the cell.

Equilibrium Potential

The neuron’s membrane potential at which the electrical and concentration gradients for a given ion balance out is called the ion’s equilibrium potential. The ion is at equilibrium at this membrane potential, meaning there is no net movement of the ion in either direction. Let’s look at sodium in more detail:

Example: Driving Forces on Sodium Ions

When sodium channels open, the neuron's membrane becomes permeable to sodium, and sodium will begin to flow across the membrane. The direction is dependent upon the electrochemical gradients. The concentration of sodium in the extracellular solution is about 10 times higher than the intracellular solution, so there is a concentration gradient driving sodium into the cell. Additionally, at rest, the inside of the neuron is more negative than the outside, so there is also an electrical gradient driving sodium into the cell.

As sodium moves into the cell, though, these gradients change in driving strength. As the neuron's membrane potential become positive, the electrical gradient no longer works to drive sodium into the cell. Eventually, the concentration gradient driving sodium into the neuron and the electrical gradient driving sodium out of the neuron balance with equal and opposite strengths, and sodium is at equilibrium. The membrane potential of the neuron at which equilibrium occurs is called the equilibrium potential of an ion, which, for sodium, is approximately +60 mV.

Calculate Equilibrium Potential with Nernst Equation

The gradients acting on the ion will always drive the ion towards equilibrium. The equilibrium potential of an ion is calculated using the Nernst equation:

The Nernst Equation

[latex]E_{ion}= \displaystyle \frac{61}{z} log \frac{[ion]_{outside}}{[ion]_{inside}}[/latex]

The constant 61 is calculated using values such as the universal gas constant and temperature of mammalian cells

Z is the charge of the ion

[Ion]inside is the intracellular concentration of the ion

[Ion]outside is the extracellular concentration of the ion

An Example: Sodium's Equilibrium Potential

[latex]E_{ion}= \displaystyle \frac{61}{z} log \frac{[ion]_{outside}}{[ion]_{inside}}[/latex]

For Sodium:

z = 1

[Ion]inside = 15 mM

[Ion]outside = 145 mM

[latex]E_{ion}= \displaystyle \frac{61}{1} log \frac{145}{15} = 60 mV[/latex]

It is possible to predict which way an ion will move by comparing the ion’s equilibrium potential to the neuron's membrane potential

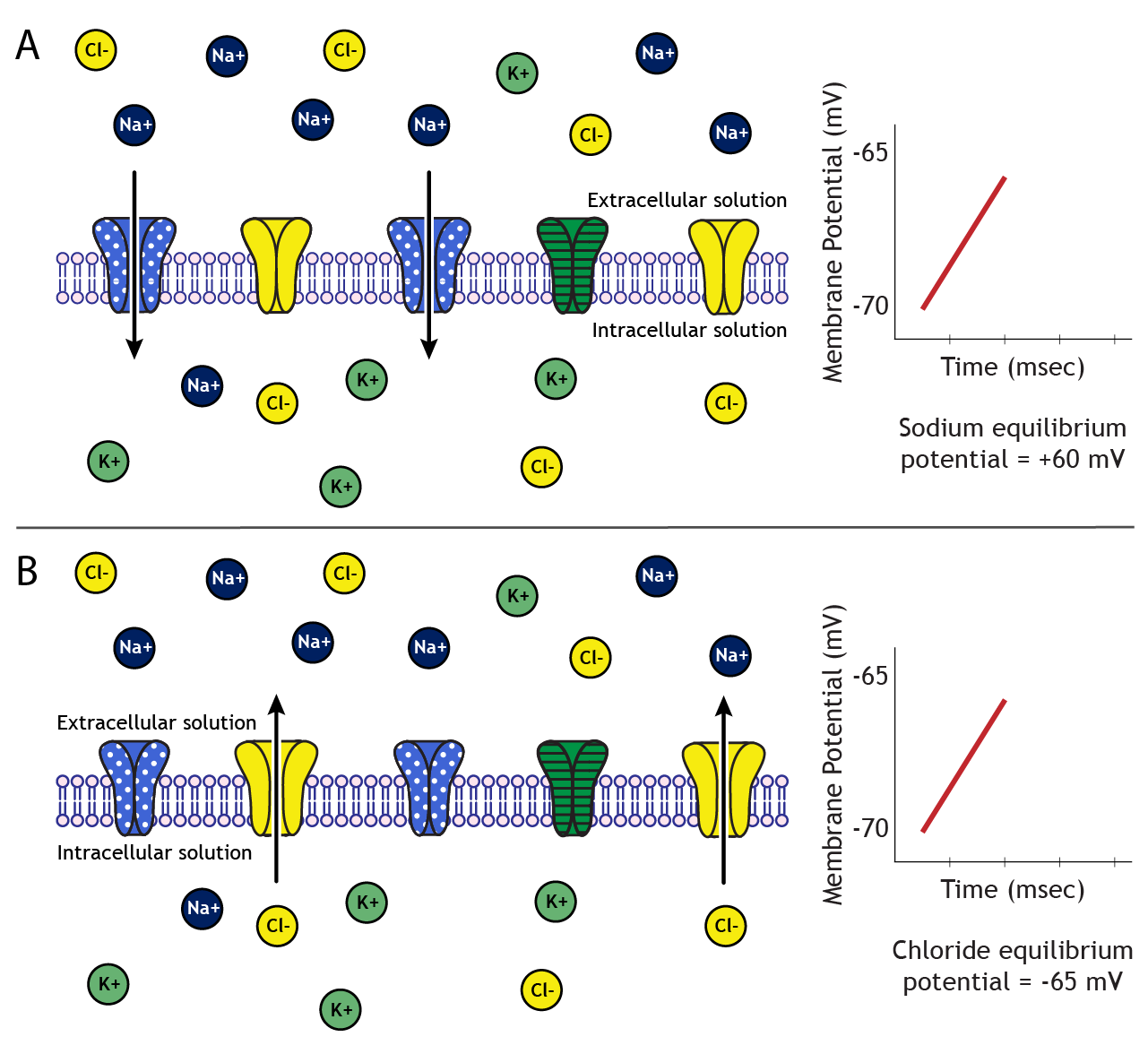

Predict Ion Movement by Comparing Membrane Potential to Equilibrium Potential

Let's assume we have a cell with a resting membrane potential of -70 mV. Sodium's equilibrium potential is +60 mV. Therefore, to reach equilibrium, sodium will need to enter the cell, bringing in positive charge. On the other hand, chloride's equilibrium potential is -65 mV. Since chloride is a negative ion, it will need to leave the cell in order to make the cell's membrane potential more positive to move from -70 mV to -65 mV.

Conclusion

Membrane potential reflects the interplay between ion gradients and neuronal permeability. Understanding these principles is critical for exploring how neurons communicate and maintain homeostasis.

Concentration and Equilibrium Potential Values

We will use the following ion concentrations and equilibrium potentials:

| Ion | Inside concentration (mM) | Outside concentration (mM) | Equilibrium Potential |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium | 15 | 145 | +60 mV |

| Potassium | 125 | 5 | -85 mV |

| Chloride | 13 | 150 | -65 mV |

Table 3.1. Intra- and extracellular concentration and equilibrium potential values for a typical neuron at rest for sodium, potassium, and chloride.

Key Takeaways

- Membrane potential is the voltage difference between the inside and outside of the neuron, typically around -65 mV at rest.

- Moving the membrane potential toward 0 mV is a decrease in potential; moving away from 0 mV is an increase in potential

- The distribution of ions inside and outside of the cell at rest vary among the different ions; some are concentrated inside, some are concentrated outside

- Electrochemical gradients determine the direction of ion flow, with ions moving toward equilibrium potential.

- The equilibrium potential for each ion is calculated using the Nernst equation, balancing electrical and concentration gradients.

Test Yourself!

Try the quiz more than once to get different questions!

- Define resting membrane potential (Vm) of a cell.

- Explain the differences between the resting membrane potential and the equilibrium potential.

- Using the concentration values from the table below, calculate the equilibrium potential of potassium using the Nernst equation. Table A.1. Intra- and extracellular concentration (mM) and equilibrium potential (mV) values for ions present in the Thinking Cell.

Ion Inside concentration (mM) Outside concentration (mM) Equilibrium Potential (mV) A- 6 125 -65 B+ 12 120 +60 D+ 125 5 -84 E++ 0.00001 1.5 +155