33 Neural Control of Stress

It is likely every reader of this chapter has experienced some form of stress, perhaps due to a big exam, a looming deadline, or an unplanned interaction with a spider. The physical reactions to stress, like increased heart rate and breathing, are a result of brain activation.

Types of stress

Stress is often split into two categories: physical and psychological. Physical stress can be caused by trauma, illness, or injury. Blood loss, dehydration or allergic reactions are examples of physical stressors. Psychological stress has an emotional and mental component. Fear, anxiety, and grief are examples of psychological stress. The neural circuits involved in responding to the different stressors are overlapping but separate.

Stress response systems

The body has two main systems for responding to stress: the autonomic nervous system and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. The autonomic nervous system response occurs very quickly because it is synaptic in nature and is responsible for the “fight or flight” response, which stimulates heart rate and breathing and inhibits digestion. The HPA axis is a hormonal response, so it is a slower response relative to the autonomic system. Its downstream effects also promote energy use.

Neural Control

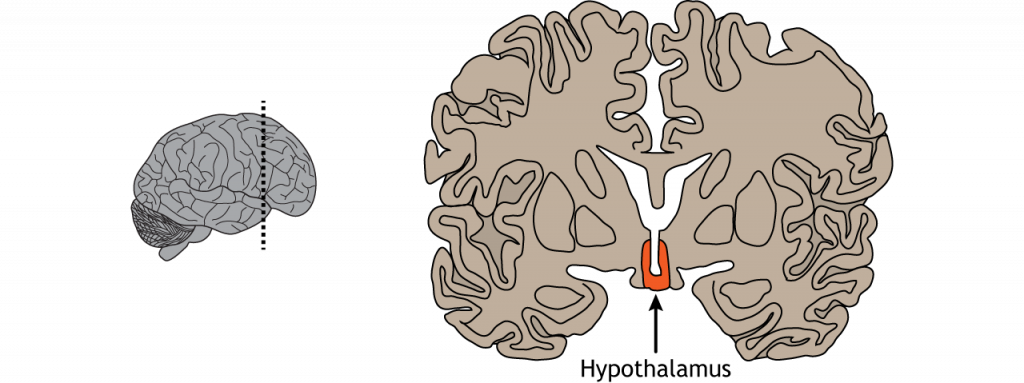

Hypothalamus

The hypothalamus plays a critical role in stress, activating both the autonomic and hormonal responses. The hypothalamus is a region right above the brainstem on either side of the 3rd ventricle. The hypothalamus manages hormone release in the body and maintains homeostasis; this small structure is critical for numerous functions including hunger and thirst, temperature control, regulation of blood composition, sleep, reproduction, and stress.

View the hypothalamus using the BrainFacts.org 3D Brain

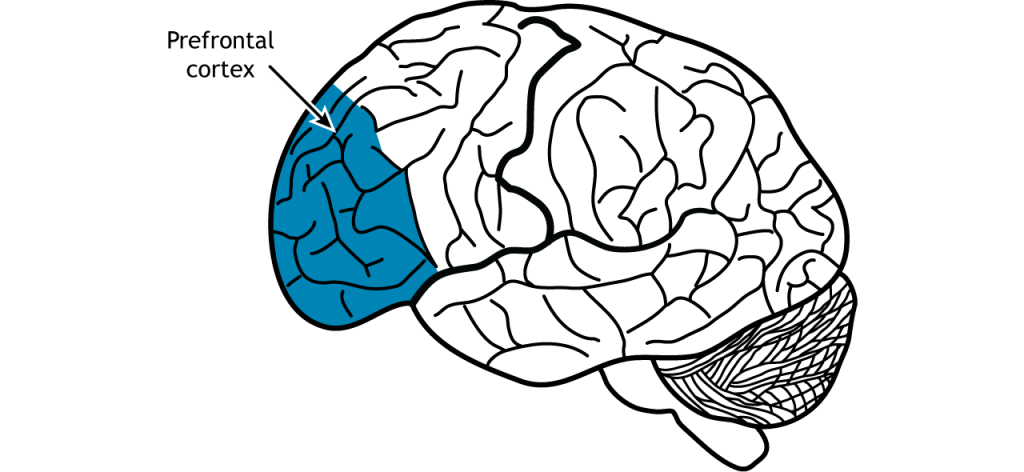

Although the hypothalamus directly controls the body’s response to stress, it is influenced by activity in other regions of the brain. When information from the environment is processed, activity is seen in the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and amygdala. These regions have direct and indirect connections to the hypothalamus. The prefrontal cortex plays an executive decision-making role, the hippocampus places events in context with previous memories, and the amygdala assesses a wide range of stimuli for their potential ability to cause harm and places an emotional value on them.

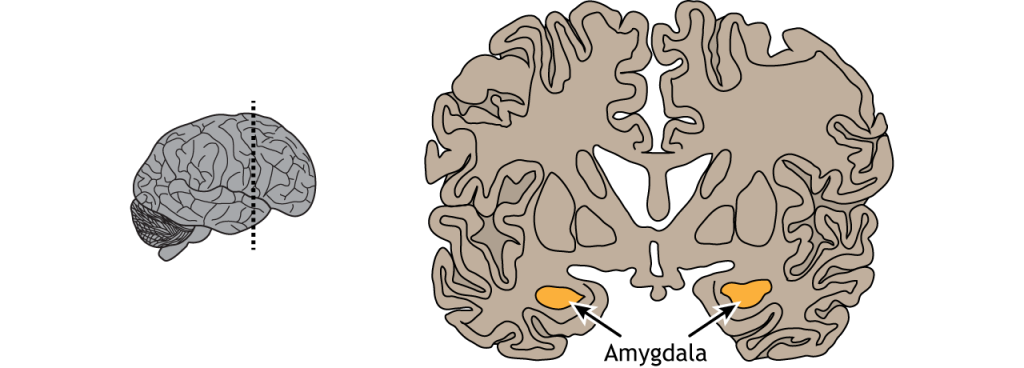

Amygdala

The amygdala is located medially in the temporal lobe. The amygdala, which means “almond” in Latin, is responsible for the processing of emotions and consolidating emotional memories. It is especially active during fear learning and evaluates the salience, or importance, of a situation. For instance, when we look at frightened faces, our amygdala is more activated than when we see neutral faces. Conditions such as anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder are all linked to amygdala dysfunction.

View the amygdala using the BrainFacts.org 3D Brain

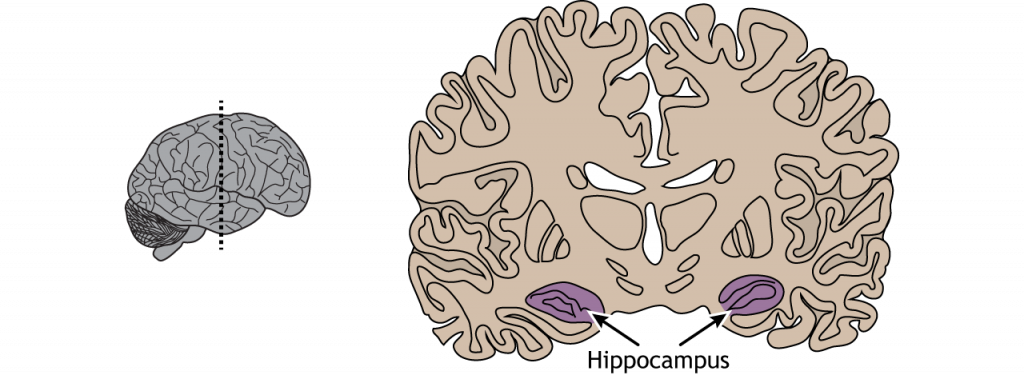

Hippocampus

Just posterior to the amygdala lies the hippocampus. The hippocampus, which means “seahorse” due to the similarity between its shape and the animal, is important in the long-term consolidation of memories, spatial navigation, and associating contextual cues with events and memories.

View the hippocampus using the BrainFacts.org 3D Brain

Prefrontal Cortex

Finally, the prefrontal cortex, which is located in the front of the brain in the frontal lobe, contributes to higher level cognitive functions like planning, critical thinking, understanding the consequences of our behaviors, and is also associated with the inhibition of impulsive behaviors. The prefrontal cortex is one of the last brain regions to fully develop and may not be fully developed until an individual reaches their mid-twenties. Experts think this might explain why teens are more likely than adults to participate in risky behaviors.

View the prefrontal cortex using the BrainFacts.org 3D Brain

Key Takeaways

- There are two systems that manage physical responses to stress: the autonomic nervous system and the HPA axis

- The hypothalamus is located on either side of the 3rd ventricle, inferior to the thalamus and directly controls both the autonomic nervous system and the HPA axis

- The amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex all influence the activity of the hypothalamus

Test Yourself!