Copyright Basics

David Bamman; Brandon Butler; Kyle K. Courtney; and Brianna L. Schofield

Copyright Basics

Copyright law is part of a legal system that covers both creation and use. Here, we will cover the copyright basics: what copyright is, what copyright protects, and how long copyright protection lasts. Additionally, copyright law is filled with exceptions and exemptions that strike a balance between the exclusive rights granted to creators and the rights of many users, including TDM researchers. It is critical that TDM researchers understand both the rights and the exceptions, with an emphasis on fair use, which—in the TDM context—is one of the most important rights that provides a legal justification for using the material that drives a TDM project. However, before the exceptions (which are covered in a later section), let us start with the copyright basics.

In 1710, the English parliament passed the Statute of Anne. This new law gave authors, for the first time in history, an economic incentive to create new works: Authors had control of their own works, and the copies made, via a limited economic monopoly—not unlike our modern understanding of copyright. This captured the first balance between authors’ rights and the public benefit of copyright, when works drop into the public domain. This temporary economic right was enough incentive for authors to continue to create new works. And, of course, when the rights expired (after 14 years), the work would drop into the public domain and anyone could use the work thereafter without permission. This encapsulated the cycle of copyright: creation, control, and expiration, with the hope that further works could be created using what dropped into the public domain. In fact, the Act starts with the language: “An Act for the Encouragement of Learning”.

This concept moved into the U.S. system in our Constitution. Certainly, the members of the United States Constitutional Convention were aware of the ideas of control and censorship as the U.S. emerged from English rule. In 1790, pursuant to their Constitutional authority under Constitutional Clause in article 1, section 8, clause 8: “To promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries;”, the Congress passed, and George Washington signed, the first copyright law in the United States. It was also titled “An Act for the Encouragement of Learning” and featured the same balance that the English had revolutionized with the Statute of Anne: an incentive of a limited economic monopoly granted to authors over their works, followed by the expiration of those rights when the work then would drop into the public domain.

The current copyright law on the books is based on that initial 1790 law, but now it is in the U.S. code as the Copyright Act of 1976. It protects original works of authorship that are fixed in any tangible medium of expression.

But what is an “original work of authorship”? An original work must embody some minimum amount of creativity.

Courts have held that almost any spark beyond the trivial will constitute sufficient originality. On the other hand, the Supreme Court ruled in 1991 that a garden variety alphabetical, white pages telephone book lacks the minimum creativity necessary for copyright protection. This is called the Feist case. The U.S. Supreme Court held in Feist Publications v. Rural Telephone Service that copying of a white pages book was not infringement because there was no existing copyright. However, although facts themselves are not copyrightable, the way the items are categorized and arranged may be original enough to satisfy the originality requirement.

Ultimately, this creativity threshold is also touched upon in another part of the Copyright Act, section 102(b), which states that copyright’s threshold for originality does extend to any idea, procedure, process, system, method of operation, concept, principle, or discovery

. From this, we gather an important point for authors: facts are not copyrightable.

But, beyond creativity, what is copyright, really? Is it a “bundle of rights”; a limited economic monopoly for authors; or, in the Constitutional narrative, is it a system to promote the progress of science and the useful arts

?

Well for copyright to work, it has to be all three. The cycle of creation, dissemination, and expiration of rights into the public domain is a critical component of copyright law. Without this balance, the system loses its value, or prevents the public from receiving the benefit of the bargain. The bargain is made by granting limited economic monopolies to incentivise creation, and then—after expiration of the monopoly—the benefit is effectively giving that material to the public for unimpeded use, thus inspiring more works to be harnessed and used.

When a work is creative and fixed, creators automatically get this exclusive bundle of rights. These are the rights: to reproduce the work copies; to prepare derivative works; to distribute copies; to perform the copyrighted work publicly; and to display the copyrighted work publicly.

In 1790, when George Washington signed our country’s first copyright law into existence, copyright protection was for books, maps, and charts. However, under the Copyright Act of 1976, the subject matter of copyright has been extended into these eight extensive categories: (1) literary works; (2) musical works, including any accompanying words; (3) dramatic works, including any accompanying music; (4) pantomimes and choreographic works; (5) pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works; (6) motion pictures and other audiovisual works; (7) sound recordings; and (8) architectural works. As Congress indicated in the creation of these categories, there is a great deal of material that has the potential to be protected by copyright.

Occasionally, we learn about copyright by understanding what’s not copyrightable. For example, there are other parts of intellectual property law that are not under the umbrella of copyright. Slogans and logos, for example, are part of trademark law. Trademark law is generally all about what the mind of the consumers think as the source of the material when they see a logo. Patent law covers new and useful ideas such as processes, methods, and systems that are separate from copyright. Secret formulas and recipes that are not disclosed to the public are generally considered trade secrets. They derive economic value by not being disclosed to the public. Then, of course, there’s raw data. As we know from Feist, our white pages telephone book case, you can’t copyright a fact. Applying that holding here, raw data then—viewed as a set of facts—is uncopyrightable.

In order to understand copyright, you need to know these six things: that creators get copyright if the work is original, creative, and fixed in a tangible medium of expression; that no registration is required to get copyright—the work is automatically granted protection under copyright if it’s creative and fixed; that the grant of rights to the author is represented by the exclusive bundle of rights in section 106; that there is a wide range of protected works; and that they have a long term of protection. However—as we will cover—despite all of these rights, there are numerous exceptions and limitations. The focus of our inquiry for TDM will be section 107: Fair use.

However, before we move to the exceptions, we will cover a critical part of the copyright cycle: the public domain. When copyright was first passed by Congress in 1790, Congress set a term of protection for 14 years, with a potential of an additional 14 years if the creator renewed the copyright. In 1909, Congress doubled that timeline and copyright moved to a 28-year term of protection with a potential 28-year renewal. In 1976, in accordance with harmonizing international copyright law and as part of the Copyright Act of 1976, the term was set to life of the author plus 50 years. In 1998, that term was expanded by Congress for an additional 20 years. And so, copyright today is measured by the life of the author plus 70 years, but what happens after expiration? Our next segment will cover that which is in the public domain.

The Public Domain

The previous section of this chapter covered what copyright is, what copyright protects, and how long copyright protection lasts. This section addresses the flip side of copyright: the public domain.

In copyright, the public domain is the commons of material that is not protected by copyright. Anyone is free to use, copy, share, and remix material that is in the public domain. The public domain includes works for which the copyright has expired, works for which copyright owners failed to comply with “formalities,” and things that are just not copyrightable at all. This section discusses each of these categories in turn.

A word of caution: Some people mistakenly think that the “public domain” means anything that is publicly available—this is wrong. The public domain has nothing to do with what is readily available for public consumption. This means that just because something is on the internet, it doesn’t put it in the public domain.

Remember that under today’s copyright laws, a work of creative, original expression simply needs to be fixed in a tangible medium

to be eligible for copyright protection. If Philippa Photographer takes a photograph and puts it online on her blog, it doesn’t mean that she is also granting you permission to reuse it. The default is that Philippa’s photo is protected by copyright and not in the public domain.

Copyright Expiration

One way content enters the public domain and becomes free of copyright protection is through copyright expiration.

Copyright protects works for a limited time. After that, copyright expires and works fall into the public domain and are free to use. Under United States copyright law, in 2021 (the year this book is being released) all works first published in the US in 1925 or earlier are now in the public domain due to copyright expiration. That said, unpublished works created before 1926 could still be protected by copyright. Under today’s copyright laws, works created by an individual author today won’t enter the public domain until 70 years after that author’s death.

When copyright does expire, the work is in the public domain and there are no copyright restrictions. For example, the book Alice in Wonderland is in the public domain, as are New York Times articles from the 1910s, because their term has expired. This means anyone may do anything they want with the works, including activities that were formerly the exclusive right

of the copyright holder, like making copies and selling them.

Failure to Comply with Formalities

Another way a work may enter the public domain is through a failure to comply with formalities.

Copyright law used to require copyright owners to comply with certain requirements called “formalities” in order to secure copyright protection. These formalities included things like requiring the copyright owner to mark the work with a copyright notice and renew the initial term of copyright. These requirements existed in some form through March 1989. Because many authors failed to comply, many works from between 1926 and March 1989 may be in the public domain. But this analysis needs to be done on a case-by-case basis based on the facts surrounding a particular work. In some cases, a fair use analysis may be easier than making a conclusion about the copyright status of a work. (Fair use is discussed later in this chapter.)

If a work is in the public domain for failure to comply with formalities, as with copyright expiration, there are no copyright restrictions.

Uncopyrightable Subject Matter and Other Exclusions

In addition to copyright expiration and a failure to comply with formalities, copyright law also sets out things that are simply not protected by copyright, and those things are also in the public domain. This goes back to a point about the purpose of copyright: The public domain is important to the production of creativity; authors need these essential building blocks with which to work.

For example, facts are a category of things that are not copyrightable—even if those facts were difficult to collect. For instance, suppose that a historian spent several years reviewing field reports and compiling an exact, day-by-day chronology of military actions during the Vietnam War. Even though the historian expended significant time and resources to create this chronology, the facts themselves would be free for anyone to use. That said, the way that the facts are expressed—such as in an article or a book—is copyrightable.

Under United States copyright law, other types of works and subject matter do not qualify for copyright protection include: names, titles, and short phrases; typeface, fonts, and lettering; blank forms; and familiar symbols and designs. It is worth noting that other areas of intellectual property, such as patent or trademark law, could provide protection for categories that are not eligible for copyright protection.

The Copyright Act also provides that works created by the United States federal government are never eligible for copyright protection, though this rule does not apply to works created by U.S. state governments or foreign governments. Under the government edicts doctrine: judicial opinions, administrative rulings, legislative enactments, public ordinances, and similar official legal documents are not copyrightable for reasons of public policy.

Copyright, Licensing, and Permissions

You can learn about licenses in more detail in the Licensing chapter of this book, but copyright and licensing are so closely connected that we think it’s important to say a bit about them here, too.

A License Grants Permission and May Limit Your Rights, Too

A license is a grant of authorization from a copyright holder to exercise one of their exclusive rights—in a research library context, typically the license is to copy or display protected works on your computer. Databases, journal literature, and other electronic content is often made available under a license either directly to the user or to an institution (typically a library) on behalf of its users. The license tells you which uses have been authorized, and authorization is often conditioned on the licensee doing certain things (most importantly for commercial entities: paying a fee!).

A license may also include promises by the institution or the user not to engage in certain uses, or to only use licensed content under certain circumstances.

What this means for researchers is that your institution may already have a license that defines what sorts of uses you can make of licensed content. You’ll need to read the license, or talk to someone who understands the license terms, to learn more about what uses are possible. You may also need to negotiate a new license to enable your use, especially if you require special kinds of access to a vendor’s content in order to conduct your research.

Creative Commons and Other Open Licenses

Some works are available under open licenses that allow anyone to make specific uses of copyrighted works without the need to pay or seek additional permission from the owner. Creative Commons (“CC”) licenses are the most well-known open licenses. Creative Commons is a nonprofit organization that offers a simple, standard way to grant copyright permissions for creative works and a suite of license options that lets authors impose some commonly-sought limitations on would-be users. Instead of the “all rights reserved” default, copyright owners can apply a CC license that allows others to use and share their works without seeking permission. It is important to pay attention to the specific terms of the license: almost all of the CC licenses require attribution, some can require you to “share alike” (i.e., to attach the same license to any work you create using the licensed work), and some restrict commercial uses or the creation of derivative works (like translations). For example, a work marked CC-BY-NC means that it is licensed for other people to use and share as long as the work is appropriately credited, but commercial uses are not allowed.

Creative Commons also offers a tool, CC0, that allows a copyright owner to waive all copyrights (and some related rights) in works. Because it is a complete waiver of rights, CC0 doesn’t require attribution.

CC licenses are especially common in the academic world and research-funders increasingly require their grantees to use them, but even non-academic works may be made available under CC licenses. For example, some museums distribute photographs of works in their collections under open licenses.

Bottom line: If works are made available under a public license, then (just like any other license) these works can be used in ways that comply with the terms of the license. If a project involves works that are made available under a license, including a public license (like a CC license), these works can certainly be used in ways that comply with the terms of the license. If your use is beyond the terms of the license, or forbidden, things get more complicated. This issue will be discussed further in the chapter on licensing.

Fair Use: A Critical Copyright Exception

Imagine if all creators had to wait for a copyrighted work to be in the public domain before they used that work, or if scholars always had to seek permission to use or quote and that permission could be denied with no recourse? Happily, copyright law gives us the flexibility to allow some uses that are made during the copyright term without permission. One of the most famous of all the copyright limitations in the Copyright Act does just that: the fair use exception.

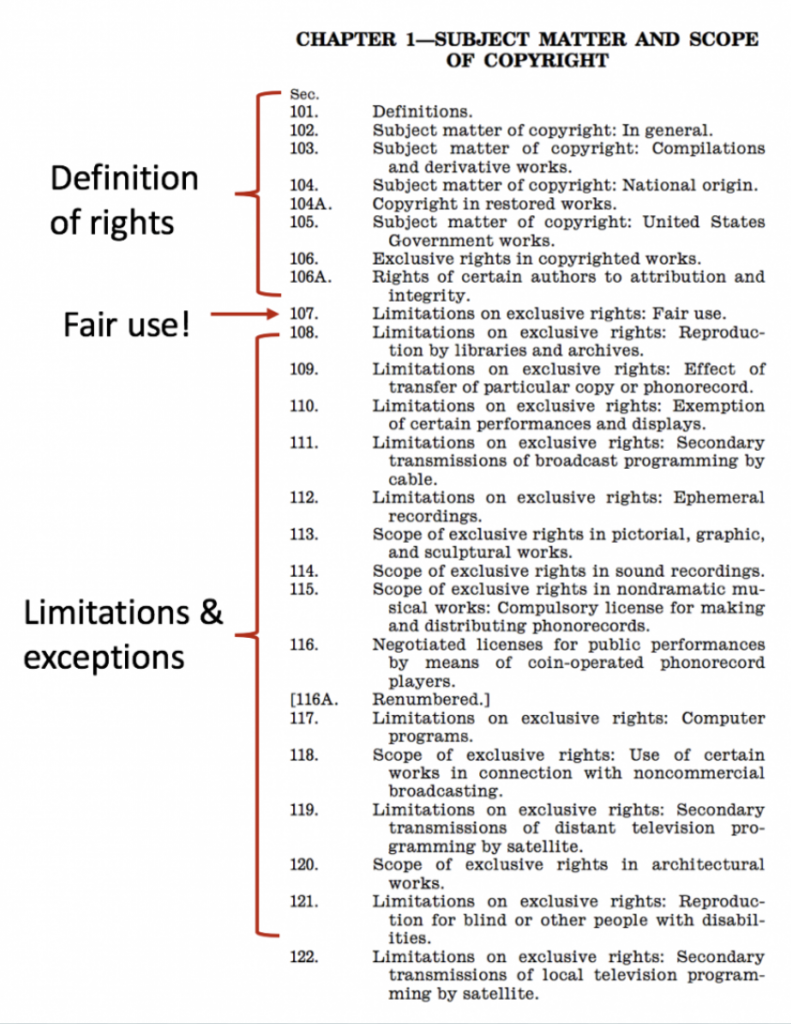

Under fair use, a person may use certain amounts of copyrighted material without permission from the copyright owner in some circumstances. The doctrine itself was rooted in both English and U.S. case law, but was eventually codified in section 107 of the U.S. Copyright Act. Fair use, as you can see in the image below, sits in the middle of the organized balance in the Copyright Act; it is squeezed right between the exclusive rights and more specific exceptions.

Fair use is a user’s right that allows individuals to exercise one or more of the exclusive bundle of rights of the copyright owner without obtaining the permission from that copyright owner and without the payment of any license fee.

To decide whether a use is fair, courts must consider at least four factors that are specifically mentioned in the Copyright Act.

17 U.S.C. §107

Notwithstanding the provisions of sections 106 and 106A, the fair use of a copyrighted work, including such use by reproduction in copies or phonorecords or by any other means specified by that section, for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright.

In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use, the factors to be considered shall include—

- the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

- the nature of the copyrighted work;

- the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

- the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

The first factor is the purpose and character of the use. Here, courts ask whether the material has been transformed by adding new meaning or expression, or whether value was added by creating new information, meaning, or understanding. When a work is used for a different purpose than the original, the factor will likely weigh in favor of fair use. If it simply acts as a substitute for the original work, the less likely it is to be fair. Courts may also look at whether the use of the material was for commercial or noncommercial purposes under this factor, but this is rarely a determinative consideration.

The second factor looks at the nature of the copyrighted work. Here, courts look at whether the copyrighted work that was used is creative or factual in nature (a song or a novel vs. technical article or news item). The more factual the work, the more likely this factor will weigh in favor of fair use. On the flip side, the more creative the copyrighted work, the more likely this factor is to weigh against fair use. Courts may also consider whether the copyrighted work is published or unpublished. If the work is unpublished, this factor is less likely to weigh in favor of fair use. Note that this factor has been slightly deemphasized by the courts over the last twenty years.

The third factor is the amount and substantiality of the portion taken. Under this factor, courts look at how much of the work was taken, both quantitatively and qualitatively. Quantitatively, courts look at how much of the original work was used (e.g., all the pages, the entire work of art). Qualitatively, some courts look at whether the “heart” of the work was taken (i.e., the essential bit of the work; why people want to engage and acquire the work). The more that is taken, quantitatively and qualitatively, the less likely the use is to be fair. That said, copying a full work can absolutely be a fair use depending on the circumstances.

Finally, the fourth factor is the effect of the use on the potential market. The essential question courts ask here is whether this use will undermine the market, or the potential market, for the work that was copied. In assessing this factor, courts consider whether the use would hurt the market for the original work (for example, by displacing sales of the original). There’s a lot more nuance to this factor, but let’s move ahead to transformative fair use.

Transformative Fair Use

In 1841, the U.S. decided its first fair use case. As case law developed, so did new and different fair use theories. One of the more interesting developments in fair use litigation was the emergence of transformative fair use. Use of any copyrighted materials is substantially more likely to pass fair use muster if the use is transformative. A work is transformative if, in the words of the Supreme Court, it “adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning, or message.” Transformative fair use is still a use without permission, but it is the legal engine which drives scholarship, research, and teaching.

The last two decades has seen a shift in courts’ analysis of the fair use test in creative endeavors like these. In transformative fair use, we see the courts collapsing the traditional “four fair use factors” to ask the following questions:

- Does the new use transform the material, by using it for a different purpose?

- Was the amount taken appropriate to the new, transformative purpose?

Importantly, it helps to identify that this new transformative use has a different purpose than the original item’s purpose. For example, the original purpose of the fictional books in the Copyright Use Case was for entertainment. The new use should be for a different purpose—and arguably, the new purpose would be to add commentary or analysis that reveals a new meaning or message, altering the original works with new commentary, expression, meaning, or message.

Fair use law is well-equipped to be adaptable to various scenarios. That’s the purpose of fair use: flexibility. Fair use is not mechanically applied or even weighed equally. Courts take into account all the facts and circumstances of a specific case to decide if use of copyrighted material is fair. Scholars, librarians, lawyers, students, staff, and faculty can also use the fair use statute and legal decisions to evaluate their own fair use risk calculus for their own scenarios.