1 The Role of History in Michigan’s Trails

“Sharing the history of a place creates an added dimension for trail users. It’s like adding texture to a smooth surface. The opposite of a generic experience.”

“The addition of heritage interpretation enhances the trail experience by strengthening the connection between people and place. To illustrate this, think of the landscapes and communities that a trail passes through as a page in the middle of a book. In order for that page to make sense, you need to know what the previous chapters say. That’s what heritage trails provide—context for these places.”

—Dan Spegel, Michigan DNR Heritage Trails Coordinator, Guest Speaker in CSUS 491 Michigan Trails

Chapter Objectives and Goals

In order to appreciate Michigan’s trail system, it is important for students to have an understanding of the history of trail use in the state and to be able to appreciate the significant cultural and historical legacy of trail use by Native Americans and early European settlers. In addition, students also need to be aware of the important role in trail management that telling history along the trails plays in providing enriched trail experiences.

Key Questions to Consider as You Read this Chapter

- Several key Native American trails became the foundation for major current highways and roads—what prompted that development?

- What do we know about water trails and why did Native American tribes prefer them to land trails? What are their connections to commerce for European settlers?

- What current wetland practice led to the demise of many water trails in Michigan?

- How did trails help to develop early Michigan as a territory?

- Railroads became the preferred mode of early mass transit, and also interestingly the foundation for many of our current trails. How did this come about?

- What key Michigan statute helps promote both trails and trail use? Why is this statute so important for Michigan?

- What are the main trails in Michigan that were formed from railroad conversions? What are some advantages and disadvantages of utilizing old railroad beds for trails?

- What are some organizations in Michigan that have helped shape Michigan trails, and what roles have they played?

- What is Michigan’s Heritage Trail Program and what was the genesis of that program?

- Why is it so important that we promote history and culture in our trail system?

Introduction

Michigan’s unique and nation-leading trail system is steeped in rich historical and cultural context. History provides a unique backdrop for this trail system, helping to interpret and promote the legacy of Michigan’s people and their culture and traditions.

Telling stories of Michigan’s culture and history has many benefits for the state and its citizens. It allows trail users to connect with their surroundings on a deeper level and to sense the impact that prior generations of Michiganders have had on the state. Some observers have likened this effect to “being able go back in time to feel what life was like hundreds of years ago in early Michigan.”

History-telling helps stimulate a deeper personal experience of a place. Adding history-based interpretative programs on trails helps perpetuate stories of the past and keep them alive for future generations. This helps trail users better understand the history of a place and also helps to cultivate pride in local heritage by allowing people to understand their community’s role in helping to develop and grow a place.

Telling history on trails also provides a unique and enduring opportunity for local citizens to engage in interpretive work by allowing them to be engaged in local history-telling programs. There are unique examples of this throughout Michigan’s trail system as citizens and citizen organizations at the local level engage in meaningful history-telling programs.

To fully understand the value and opportunities for history-telling, it’s vital to appreciate the many events and people that have shaped the history of Michigan’s trails.

A History of Michigan’s Trails

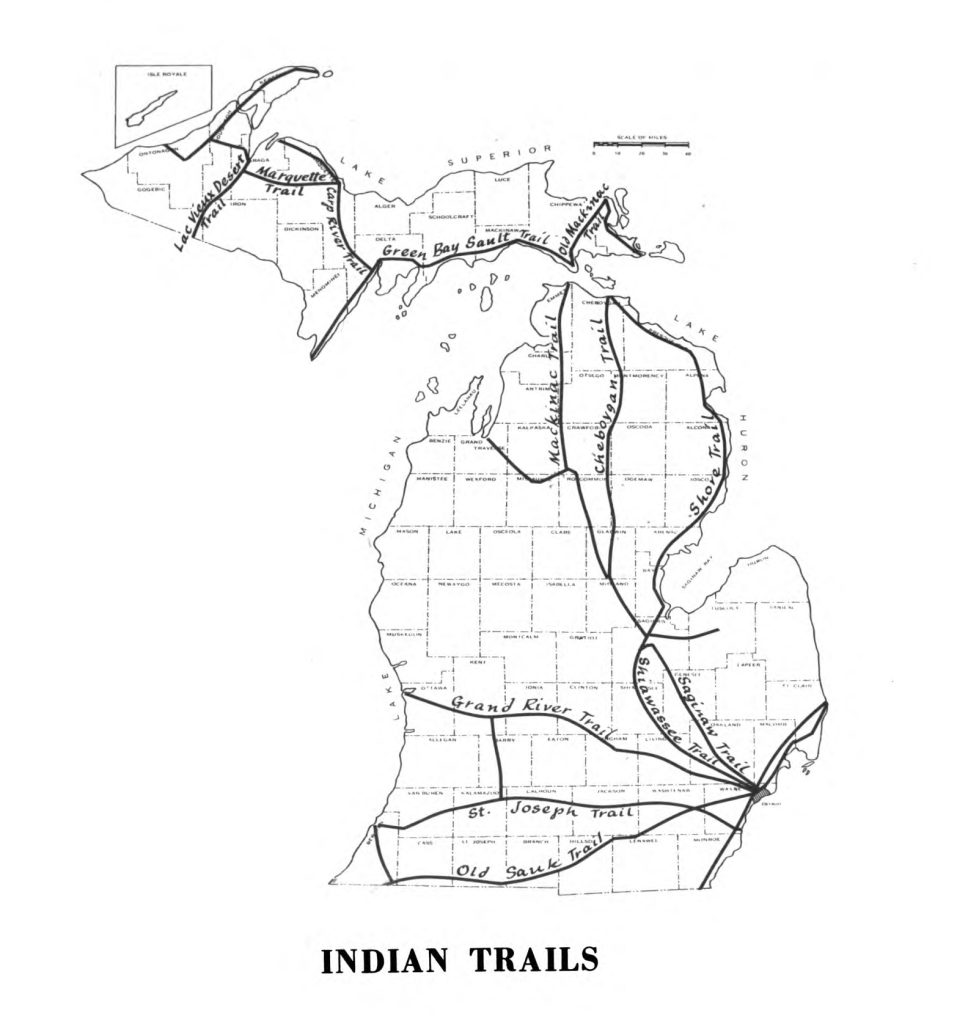

The Anishnaabek are a group of culturally related indigenous people that live in the Great Lakes region. In Michigan, most Anishinaabe people belong to three nations: the Chippewa, the Odawa and the Potawatomi. Prior to European settlement, the Anishnaabek created a vast network of land and water trails that laid the foundation for Michigan’s current trail system.

Anishinaabe trails were often quite narrow and, in many cases, may have been nothing more than simple rutted paths that were about 12 to 18 inches wide. The narrow paths were just wide enough for Native Americans to walk in single file, often to try to disguise their numbers because of concern for other people in the area (Hardy 2021).

The pathways used lands that were most easily traversed and crossed rivers and streams where they were the shallowest. Often stepping stones were placed across these rivers both to assist with crossing and help mark areas suitable for crossing.

Many of the Native American trails found in Michigan were considered to be part of the Great Trail Network, a trade and transportation route that extended hundreds of miles to the Eastern Seaboard. Larger foundational trails were connected to smaller tributary trails that served to provide access to a variety of seasonal hunting and fishing areas, salt wells, and copper and mineral mines. The trail system was used primarily for transportation, to access gathering places, and to extend commerce and trade routes (Hardy 2024).

Interactive map of Michigan tribal trails prior to 1820 (Hardy 2024).

Major Land Routes

Many of these early Native American footpaths served as the foundations for Michigan’s current system of roads and highways. The eight major Native American land routes were the Sauk Trail, the Saginaw Trail, the Saint Joseph Trail, the Grand River Trail, the Mackinac Trail, the Maumee-Shoreline Trail, the Shiawassee Trail, and the Cheboygan Trail.

Saint Joseph Trail

The Saint Joseph Trail is considered to be one of the most significant east-to-west trail routes in Michigan. This trail was also known as the Route du Sieur la Salle, named after the 17th century explorer who was engaged in the search for a land route across the continent to China. Today this route is shared with much of Interstate 94 and portions of US 12 and is also often referred to as Territorial Road (Hardy 2021).

Cheboygan Trail

The Cheboygan Trail was an interior northern Michigan trail that extended to the Straits of Mackinac and hugged borders of eastern forest land. State Road M-33 follows much of this trail system today (Hardy 2024).

Shiawassee Trail

The Shiawassee Trail began just west of Detroit and ran northwest until it connected to the Shiawassee River at the present-day village of Byron. This trail followed the Shiawassee River to the Saginaw River and ended in Saginaw. The city of Farmington was originally located where the Shiawassee trail crossed the River Rouge (Hardy 2024; Sewick 2016).

Mackinac Trail

The Mackinac Trail was an interior northern Michigan Trail that extended to the Mackinac Straits and bordered western forest land. Today, Interstate 75 (I-75) overlays much of this system (Bessert 2024 and Hardy 2024).

Saginaw Trail

The Saginaw Trail was a major north-to-south Sauk trail system that extended from Detroit to Saginaw. Today this trail starts at the Detroit River and heads northwest to Woodward Avenue in the city of Pontiac, continuing up what is known today as the Dixie Highway through the cities of Flint and Saginaw (Hardy 2018b; Sewick 2016).

Grand River Trail

The Grand River Trail was an east-to-west route from the cities of Grand Rapids to Detroit that Native Americans used for transportation and commerce for centuries before pioneers arrived. This trail is now generally followed by Interstate 96 (I-96) (Hardy 2024).

Sauk Trail

The Sauk Trail was a major land route that ran between the cities of Detroit and Chicago that was often referred to as the Chicago Road. It was believed to be established originally by migrating bison. In 1820 Henry Schoolcraft described the trail as a “plain horse path, which is considerably traveled by traders, hunters, and others.” Today this path or trail is known as US 12 (Hardy 2018a and Sewick 2016).

Maumee-Shoreline Trail

The Maumee-Shoreline Trail was one of the five trail routes leading out of the city of Detroit. It began at the Maumee River in Toledo, Ohio, then followed the shore through Detroit and continued north along the Detroit and St. Clair Rivers into the thumb area of Michigan. This was also part of the Great Trail Network and is considered to be one of Michigan’s first roads to be developed by early European settlers. Eventually it became a crucial military supply route during the War of 1812 that ran from Urbana, Ohio to Fort Detroit (Hardy 2022).

“Old Indian Trail”

The “Old Indian Trail” was part of an ancient trail system that dated back to about 700 BC. This trail ran from what is now the city of Cadillac to Traverse Bay and was approximately 55 miles long. Its historical significance is evident today through a marked trail system with map and guide resources available online. The majority of the markers (32 out of 33) are placed alongside roads indicating where the trail crossed. Because the trail often crosses private property, hiking is not advised. The trail is actively maintained by the Little Traverse Bay Band of the Odawa (Ettawagheshik n.d and Friends of the Old Indian Trail n.d.).

Water Routes

Native American pathways also included an extensive network of water routes, which included navigable inland rivers, streams, and lakes (along with the Great Lakes). When accessible, these water trails were typically preferred over land trails because travel was often faster and more direct (Hinsdale 1931). The Anishinaabe typically used birchbark canoes to traverse water routes. Prior to European settlement, much of Michigan was characterized by vast areas of wet and marshy lands that facilitated the use of water corridors for commerce and transportation. As European settlers arrived, wetlands were often drained for farming and development, thereby eliminating some of these early water trails.

Key Native American water routes included the Manistique-to-Whitefish Bay route, the Saginaw and Grand River basins, including Saginaw to Muskegon, Saginaw to Grand River, and Huron River to Grand River. These trails helped provide eventual connections to the important trade and commerce routes of the Mississippi River (Hinsdale 1931).

Commerce and Transportation

Trails provided significant commerce and transportation benefits for European settlers. As the French arrived in Michigan in the early 17th century, they began establishing trading posts and trading networks with Native Americans. These traders’ stores and trading posts stimulated tribal interest in European goods and provided an opportunity for Europeans to barter with Native American hunters for fur. These trading posts were almost always situated at the intersections of main trails and were usually close to major water routes.

Early visitors to the region found that often the best places to settle were sites of former Native American villages, as they were able to utilize and maintain the same trails that ran between those villages. Eventually, they expanded many of these footpaths into wagon trails and roads. In 1805, Michigan was designated a territory, and for the next 30 years, one of the territorial government’s first priorities was to create a system of regional roads to assist in the settlement of the territory. Territorial road development was aided significantly by these already well-established Native American pathways.

Rail Trails in Michigan: A Brief History

In 1832, Michigan’s first railroad tracks were laid by the Erie and Kalamazoo Railroad Company between Adrian, Michigan and Toledo, Ohio. By the late 1800s to early 1900s, Michigan’s railroad system had increased to more than 9,000 miles of active rail service with the rapid rise in the popularity of railroad use for both transportation and commerce (MDOT 2014). Railroads helped open the state to a variety of commerce opportunities, including transportation of timber resources and other freight and helped to expand transportation and development opportunities throughout Michigan.

However, as Michigan’s road system improved and the use of automobiles increased, reliance upon the use of railroads decreased in Michigan. With continued decline in rail use, many railroad corridors began to be considered for decommissioning or abandonment. At the time of this writing, only about 3,600 miles of track are still in active use in the state (MDOT 2024).

In the 1960s, early trail advocates began to appreciate the unique opportunities to use abandoned railroad corridors for trails and formally abandoned railroad corridors began to be converted into public trails. These early “rail trail” conversions provided new recreational and economic opportunities for many communities (RTC n.d.b).

The nation’s first official rail trail is the Elroy-Sparta State Trail, located in Wisconsin, which opened to the public in 1965 (Wisconsin Department of Tourism n.d.). Michigan’s first rail trail is the Haywire Grade Trail located in the Upper Peninsula, which opened in 1970 (DNR n.d.a). Today, Michigan has more than 2,500 rail trail miles—more rail trail miles than any other state (RTC 2024).

Although these rail trail conversions provided opportunities for trail development, there were also patches of opposition to rail trail development due to concerns over impact on adjacent private property rights. In many situations, adjacent property owners saw the opportunity to return those rail corridors to less intrusive uses and believed that trail conversions might increase the opportunity for trespass and vandalism. Today those fears have been largely dispelled as rail conversions have provided significant positive benefits for both adjacent landowners and nearby communities.

One of the most important Michigan statutes that has worked to incentivize conversions of abandoned railroad corridors is the Transportation Preservation Act of 1976.[1] This act allows for preservation of rail corridors for future use, and at the same time allows for those corridors to be used for trail conversions. The Michigan legislature enacted this program to both maintain control of the corridor for future rail use if necessary but also recognized the opportunities to use these corridors for recreational trails. In taking this approach, the legislature acknowledged both the value of rail use and trail use.

Some of the earliest and best-known rail trail conversions in Michigan include the White Pine Trail, the Pere Marquette Rail Trail, the Paint Creek Rail Trail, and the initial railroad conversion in Michigan—the Haywire Grade Trail in the Upper Peninsula.

White Pine Trail

The White Pine Trail follows a railroad corridor originally built by the Grand Rapids and Indiana Railroad, which provided freight and passenger services from Cincinnati, Ohio to the Straits of Mackinac. The White Pine Trail spans 92 miles and is the longest rail trail linear state park in Michigan. The White Pine Trail connects the city of Grand Rapids to the city of Cadillac, crosses five counties, and interestingly includes fourteen open deck bridges (Cadillac Area Visitors Bureau n.d.).

Pere Marquette Rail Trail

The Pere Marquette Rail Trail traces segments of the Flint and Pere Marquette Railroad between the cities of Midland and Clare that originally opened for rail traffic in 1870. This railroad corridor was used to transport supplies to and from timber companies that were harvesting many of the state’s old growth forests. It was eventually purchased by the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway in 1947 and was formally abandoned in the 1980s. The first stretch of this rail trail conversion was opened in 1993 and today the trail stretches from downtown Midland to the outskirts of Clare, a distance of approximately 30 miles (RTC n.d.c). The Pere Marquette Rail Trail is one of Michigan’s most well-known and popular trails, drawing over 170,000 visitors each year (Nelson et al 2002).

Paint Creek Rail Trail

The Paint Creek Rail Trail was converted to a trail from the former Penn Central railroad line which was abandoned in the 1970s. In 1981, this abandoned railroad corridor was purchased using Michigan Natural Resources Trust Fund (MNRTF) grant dollars along with matching community donations. Recognized as Michigan’s first fully non-motorized rail trail, it opened to the public in 1983 and is approximately 8.9 miles long (Paint Creek Trailways Commission n.d.).

Key Individuals and Organizations in Michigan’s Trail History

Michigan has a rich legacy of people and organizations that have been successful in helping spur the development of trails. These groups and individuals often share common traits of being closely connected with their community and passionate and persuasive in rallying community support behind trails.

Organizations and their impact on Michigan trails will be covered more thoroughly in a subsequent chapter. However, for the purpose of providing an understanding of the history of organizational efforts in building trails, several important organizations are mentioned here.

Michigan Chapter of the National Rails to Trails Conservancy

One of the most impactful organizations in Michigan’s trail development was the Michigan Chapter of the National Rails to Trails Conservancy (RTC). The RTC is a national nonprofit organization, dedicated to “bring[ing] the power of trails to more communities across the country” and it has served as a national voice for rail trail development since the 1980s (RTC n.d.a). The Michigan chapter of this national organization is known today as the Michigan Trails and Greenways Alliance (MTGA).[2]

During its time with RTC, MTGA helped initiate multiple rail trail projects, advocated for other rail trail conversions, helped to form numerous friends or volunteer groups, and provided statewide guidance for trail planning and development. Over 1,500 miles of rail trail conversions throughout the state came about in part due to their efforts. MTGA continues to help build and promote trails throughout the state and remains a vital force in connecting communities through trails (MTGA n.d.).

Michigan Department of Natural Resources

The Michigan Department of Natural Resources (DNR) is the centerpiece of Michigan agencies working to develop and manage trails. The DNR has been integral in developing and expanding Michigan’s expansive trail system by serving as the lead state agency to coordinate federal, state, and local resources in trail building. The department has been tasked with the management and protection of Michigan’s natural resources since its inception of 1921 when it was created as the state’s first conservation agency, the Michigan Department of Conservation (Michiganology n.d.). The department’s mission expresses its commitment to “the conservation, protection, management, use and enjoyment of the state’s cultural and natural resources for current and future generations” (DNR n.d.b).

Parks and Recreation Division

Housed within the DNR is the Parks and Recreation Division (PRD). Beginning in 1993, the parks and boating programs of the DNR merged to form this division. The PRD’s mission statement is “to acquire, protect, and preserve the natural and cultural features of Michigan’s unique resources, and to provide access to land and water-based, public recreation and educational opportunities.” The PRD’s activities include acquisition, development, and management of trails located on state-owned and managed land. The PRD currently manages more than 13,000 miles of state-designated trails and pathways (DNR 2023).

Michigan Trails Advisory Council

The Michigan Trails Advisory Council (MTAC) was created by the Michigan legislature and was a fundamental part of the legislature’s early commitment to developing a statewide system of trails under the Michigan Trailways Act.[3] This advisory council is comprised of citizen trail advocates appointed by the Governor and helps to coordinate trail development and management in various trail regions. The council meets quarterly to take public comment and hear issues in order to help provide a “citizen’s voice” to the state’s trail plan and related activities. The council is specifically tasked with making recommendations to both the Governor and the DNR (DNR n.d.c).

Other Important Organizations and Individuals

Important organizations in Michigan that have historically been active in trail work on motorized (i.e., snowmobile and off-road vehicle) trails include the Michigan Snowmobile Association and the Off-Road Vehicle Association. These organizations merged into one organization, the Michigan Snowmobile and Off-Road Vehicle Association (MISORVA).

Organizations like the Michigan Trail Riders Association (MTRA) and the Michigan Horse Council (MHC) have been leaders in equestrian trail use and trail development for many years and have promoted safe and accessible equestrian trail-based activities. For example, MTRA has long maintained the “Shore-to-Shore Trail,” a multi-use and multi-jurisdictional trail that stretches from Lake Michigan to Lake Huron, and MHC recently partnered with the DNR to sponsor a new shoreline horseback riding season at Silver Lake State Park.

The Michigan Mountain Biking Association (MMBA) and its partner organization, the League of Michigan Bicyclists (LMB) have been active in helping to promote bicycle-based activities on both natural and improved surface trails. These organizations recently merged, creating the League of Michigan Bicyclists—Michigan Mountain Biking Association Alliance.

Trails are not possible without key individual citizen-advocates that help drive support for the development and management of trails throughout the state. Although there are hundreds of individuals that are deserving of recognition for their trail work, they are too numerous to mention all here. A short representative list includes people like Dr. Bill Olson and his work on the Betsie Valley Trail, Julie Clark and the Traverse Area Recreation Trail (TART), John Morrison of the West Michigan Trails and Greenways Coalition, Roger Storm of both the DNR and the former Michigan Chapter of the Rails to Trails Conservancy, Carol Fulsher of the Iron Ore Heritage Trail, Karen Middendorp of the MISORVA, and Ron Olson of the DNR.

Other key supporters are people like Kristen Wiltfang from Oakland County, Mike Levine and John Calvert from Pinckney, Michigan, and Andrea LaFontaine, current director of the MTGA, Jason Jones of the MMBA (currently serving as Mountain biking advisor to the League of Michigan Bicyclists), Mary Bohling of Michigan State University (MSU) Extension, Andrea Ketchmark of the North Country Trail Association (NCTA), and Colonel Don Packard of the MHC. Michigan’s legacy of gubernatorial support includes trail support from Governors John Engler, Jennifer Granholm, Rick Snyder, and Gretchen Whitmer; they are examples of state leaders who have understood the value of trails for the state and helped spur the development of trails in Michigan.

History-Telling on Michigan Trails

Michigan is fortunate to have a rich history of trail development and leadership that continues to position the state as a national leader in trails. This legacy provides important opportunities for trail managers to weave history into the building and management of trails.

Many trails in Michigan include this important component of history-telling through orchestrated interpretive signage and other methods. These interpretative programs provide trail users with curated information that enables them to understand more clearly the historical, cultural, and environmental underpinnings of their surroundings. Examples of common types of interpretive features on trails include signage, interactive stations, electronic resources, and interpretive guides to help tell history and cultural heritage along the trail.

Michigan Heritage Trail Program

The most significant statewide interpretive trail program in Michigan is the Michigan Heritage Trail Program administered within the DNR. This program was the result of legislative efforts to help explain the culture and history of the state and utilize trails to help connect people with the natural and cultural heritage of trails. The program is currently being administered by Dan Spegel acting in his official capacity as the Michigan Heritage Trail Coordinator. Spegel’s work tries to add a new dimension to the trail experience by sharing the area’s natural and cultural heritage. This helps people see why these places are special and unique, and can stimulate a deeper personal experience of that place. The Michigan Heritage Trail Program has worked to create greater awareness of people’s desire to understand the place they are visiting and works to bring the “museum outdoors where more people can encounter it” (Michigan History Center n.d.a).

Kal-Haven Trail

A centerpiece of the state’s heritage trail program is the work done on one of the state’s earliest rail trail conversions, the Kal-Haven Trail, which was dedicated in 1989. The Kal-Haven Trail is 33.5 miles in length and connects the city of South Haven to the city of Kalamazoo and runs along the former route of the Kalamazoo and South Haven Railroad. Former heavyweight champion boxer Joe Lewis did his “roadwork” in the area of this route as part of his training program for a championship fight in 1948. Thirty-one interpretive panels have been installed on the trail that share the natural and cultural heritage of the area. In 2020, an innovative mobile application was implemented to allow for increased accessibility (Michigan History Center n.d.b).

A prime example of local citizen engagement in history telling is the work being done by local historians in a restored train depot in the village of Bloomingdale located along the Kal-Haven Trail. Here local historians have developed numerous exhibits that tell the story of this village that was once known for its record-setting oil production. During its heyday, Bloomingdale was among the state’s largest producers of crude oil and development flocked to the area. When the oil wells dried up, the community was left with abandoned wells and a significant decline in population. Yet, local pride still continues in honoring the legacy of this community and provides a rich backdrop for trail visitors to understand the significance of this community and its people.

Iron Ore Heritage Trail

Another well-recognized heritage trail project is the Iron Ore Heritage Trail. Multi-faceted interpretive efforts have taken place along this trail, which is 47 miles long and passes through the cities of Marquette, Negaunee, and Ishpeming. In 2019, it was designated as a Pure Michigan Trail (UP Matters Staff 2019). The Iron Ore Heritage Trail takes trail users through multiple historic sites such as the Cliffs Shaft Mine, the Ore Dock in the city of Marquette, and several old mining buildings and engine houses. Utilizing old pieces of rail and mining infrastructure along with citizen and student-based artwork, the trail provides an intriguing depiction of life as it was in this Upper Peninsula mining community (Iron Ore Heritage Trail n.d.).

Haywire Grade Trail

The Haywire Grade Trail was Michigan’s first rail trail opening in 1970. This trail follows the old Manistique and Lake Superior railroad that was originally constructed to transport timber to the mills in Manistique. In 2020, it was designated as a Pure Michigan Trail (Pietila 2020). The rail trail runs 32 miles from the village of Shingleton to Intake Park in the city of Manistique and there are interpretive signs along the trail that share the area’s natural and cultural history (DNR n.d.a).

Group Discussion Topics

Today we use trails principally to recreate and to get outdoors. Please describe some of the more significant early uses of our trails and give an example of one trail that has served as a foundation for existing routes of transportation.

As we know, there is a rich history of trails in Michigan. Please discuss how trails help to contribute to a sense of place and why providing a sense of place is so critical to providing trail users with a more enriching experience? Why is it so critical that we recall our history and how can history telling contribute to providing added diversity, equity, and inclusion in the trails that we manage? What proposal would you make to help develop a statewide system of historical trail signage and interpretative program? How would you incorporate indigenous tribes into such an interpretive program and what other sources of information would you try to include in designing the program?

References

Austin, Paul. January 27, 2022. “11 Michigan Indian Trails We Travel Everyday.” Michigan4You. Accessed March 2, 2024. https://michigan4you.com/michigan-indian-trails/

Bessert, Chris. March 4, 2024. “Historic US-16.” Michigan Highways. Accessed March 25, 2024. https://www.michiganhighways.org/listings/HistoricUS-016.html

Cadillac Area Visitors Bureau. n.d. “White Pine Rail Trail.” Cadillac Area Visitors Bureau. Accessed March 3, 2024. https://cadillacmichigan.com/project/white-pine-rail-trail/

Ettawagheshik, Frank. n.d. “The Old Indian Trail.” Cadillac Area Visitors Bureau. Accessed March 2, 2024. https://cadillacmichigan.com/old-indian-trail-cadillac-to-traverse-city/

Friends of the Old Indian Trail. n.d. “History of the Cadillac to Traverse City Old Indian Trail.” Friends of the Old Indian Trail. Accessed March 27, 2024. https://oldindiantrail.weebly.com/history.html

Hardy, Michael. 2018a. “The Great Sauk Trail.” Thumbwind. Acccessed March 2, 2024. https://thumbwind.com/2018/12/29/great-sauk-trail/

———. 2018b. “The Saginaw Trail.” Thumbwind. Accessed March 2, 2024. https://thumbwind.com/2018/12/07/saginaw-trail/?expand_article=1

———. February 21, 2021. “The Mystery of Michigan’s St. Joseph Indian Trail.” Thumbwind. Accessed March 2, 2024. https://thumbwind.com/2021/02/21/michigan-st-joseph-indian-trail/

———. October 25, 2022. “The Story of Michigan’s Shore Indian Trail – Hull’s Trace & War of 1812.” Thumbwind. Accessed March 2, 2024. https://thumbwind.com/2022/10/25/shore-indian-trail-hulls-trace/

———. February 28, 2024. “12 Native American Trails in Michigan.” Thumbwind. Accessed March 2, 2024. https://thumbwind.com/native-american-indian-trails/

Hele, Karl S. October 19, 2022. “Anishinaabe.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/anishinaabe#:~:text=While%20Anishinaabe%20is%20most%20commonly,some%20Oji%2DCree%20and%20M%C3%A9tis.

Hinsdale, Wilbert B. 1931. Archeological Atlas of Michigan. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Iron Ore Heritage Trail. n.d. “About Us.” Iron Ore Heritage Trail. Accessed March 3, 2024. https://ironoreheritage.com/about-us/

Michigan Department of Natural Resources (DNR). 2023. Parks and Recreation Division 2023-2027 Strategic Plan. Lansing: DNR. Accessed March 3, 2024. https://www.michigan.gov/dnr/-/media/Project/Websites/dnr/Documents/PRD/parks/PRDStrategicPlan2023-2027.pdf?rev=0e9855b2e7b54744b0dbd08abf87ed62&hash=0550EEEE8E458FDA0A788E1745A9FCE4

———. n.d.a. “Haywire Grade Trail.” DNR Recreation Search. Accessed March 3, 2024. https://www2.dnr.state.mi.us/parksandtrails/Details.aspx?id=405&type=SPTR

———. n.d.b. “Mission, vision, and values.” Michigan.gov. Accessed March 3, 2024. https://www.michigan.gov/dnr/about/mission

———. n.d.c. “Trails Advisory Council.” Michigan.gov. Accessed March 3, 2024. https://www.michigan.gov/dnr/about/boards/mtac

Michigan Department of Transportation (MDOT). October 13, 2014. Michigan’s Railroad History: 1825-2014. Lansing: MDOT. Accessed March 3, 2024. https://www.michigan.gov/-/media/Project/Websites/MDOT/Travel/Mobility/Rail/Michigan-Railroad-History.pdf?rev=39dfdb4445e04a87916419fc13937dd2

———. 2024. “Rail.” Michigan.gov. Accessed March 3, 2024. https://www.michigan.gov/mdot/travel/mobility/rail

Michigan History Center. n.d.a. “Heritage Trails.” Michigan.gov. Accessed March 3, 2024. https://www.michigan.gov/mhc/heritage-trails

———. n.d.b. “Kal-Haven Heritage Trail.” Michigan.gov. Accessed March 3, 2024. https://www.michigan.gov/mhc/heritage-trails/kal-haven-heritage-trail

Michigan Legislature. March 4, 2014. “Section 10.” State Transportation Preservation Act of 1976 (Excerpt): Act 295 of 1976. Accessed March 3, 2024. http://legislature.mi.gov/doc.aspx?mcl-474-60

———. September 25, 2014. “Section 72110: Michigan Trails Advisory Council.” Natural Resources and Environmental Protection Act (Excerpt): Act 451 of 1994. Accessed March 3, 2024. http://legislature.mi.gov/doc.aspx?mcl-324-72110

Michigan Trails and Greenways Alliance (MTGA). n.d. “History.” MTGA. Accessed March 3, 2024. https://michigantrails.org/history/

Michiganology. n.d. “Department of Natural Resources.” Michiganology. Accessed March 3, 2024. https://michiganology.org/dnr/

Nelson, Charles, Joel Lynch, Christine Vogt, and Afke van der Woud. February 2002. Use and Users of the Pere Marquette Rail-Trail in Midland County Michigan. East Lansing: Michigan State University. Accessed March 3, 2024. https://www.peremarquetterailtrail.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/16/2020/11/PM-Trail-Use-Report.pdf

Paint Creek Trailways Commission. n.d. “Paint Creek Trail.” Paintcreektrail.org. Accessed March 3, 2024. https://paintcreektrail.org/wordpress/about/trail-history/

Pietila, Alissa. February 20, 2020. “Haywire Grade named a Pure Michigan Trail in 50th year.” TV6. Accessed March 3, 2024. https://www.uppermichiganssource.com/content/news/Haywire-Grade-named-a-Pure-Michigan-Trail-in-50th-year-568044561.html

Rails to Trails Conservancy (RTC). 2024. “Michigan.” Rails to Trails Conservancy. Accessed March 3, 2024. https://www.railstotrails.org/state/michigan/

———. n.d.a. “About RTC.” Rails to Trails Conservancy. Accessed March 3, 2024. https://www.railstotrails.org/about/

———. n.d.b. “History of RTC and the Trails Movement.” Rails to Trails Conservancy. Accessed March 3, 2024. https://www.railstotrails.org/about/history/

———. n.d.c. “Pere Marquette Rail Trail.” TrailLink. Accessed March 3, 2024. https://www.traillink.com/trail/pere-marquette-rail-trail/

Sewick, Paul. January 19, 2016. “Retracing Detroit’s Native American Trails.” Detroit Urbanism. Accessed March 2, 2024. https://detroiturbanism.blogspot.com/2016/01/retracing-detroits-native-american.html

University of Michigan Library Digital Collections. n.d. “Native American Footpaths Throughout Michigan.” In the digital collection Students on Site. Accessed March 2, 2024. https://quod.lib.umich.edu/s/sos/x-107/footpath

UP Matters Staff. June 20, 2019. “Iron Ore Heritage Trail chosen as Pure Michigan Designated Trail.” UP Matters. Accessed March 3, 2024. https://www.upmatters.com/news/local-news/iron-ore-heritage-trail-chosen-as-pure-michigan-designated-trail/

Wisconsin Department of Tourism. n.d. “The Elroy-Sparta State Trail: America’s First Rails-to-Trails Project.” Travel Wisconsin. Accessed March 3, 2024. https://www.travelwisconsin.com/article/road-and-multi-use-trails/article/road-multi-use-trails/article/linear-bike-trails/the-elroy-sparta-state-trail-americas-first-rails-to-trails-project#:~:text=The%20Elroy%2DSparta%20State%20Trail,even%20tunnels%20carved%20through%20rock