17 Protein Synthesis I: Transcription

Andrea Bierema

Learning Objectives

Students will be able to:

- Explain the processes necessary for transcription to begin.

- Explain how DNA is transcribed to create an mRNA sequence.

- Describe the role of polymerase in transcription.

- Recognize that protein synthesis regulation (i.e., changes in gene expression) allow cells to respond to changes in the environment.

- Explain which gene-expression regulatory factors are at play for transcription.

Overview

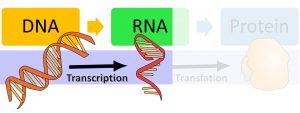

This chapter focuses on how transcription works; that is, how information coded in the DNA molecule is read to create an mRNA sequence. Please see the previous chapter for a general overview of transcription and DNA and RNA bases before continuing to read this chapter.

The Process of Transcription: A First Look

Let’s first look at a basic overview of what the process of transcription looks like. At the beginning of the following video, you will see that transcription is regulated by a variety of proteins. By “regulation”, we mean that certain proteins are needed for transcription to start and some proteins can even prevent transcription from happening. Transcription is happening throughout your body all of the time, but not every gene is constantly being transcribed in every cell; it is regulated by different proteins and depends on which proteins your body needs in which cells.

Exercise

Now that you have watched a basic overview of transcription, test your knowledge with the following activity in which you will place the following transcription steps in the correct order.

Role of the Polymerase

The polymerase is an enzyme—and a protein—that aids in the transcription process. The polymerase was depicted in the previous video. Now let’s look more closely at what is happening within the polymerase in relation to the steps described previously.

Transcription Regulation

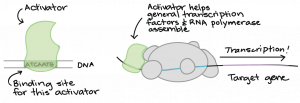

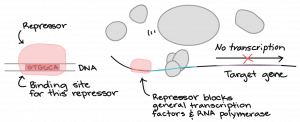

The overview above depicted components of transcription regulation. Basically, there are proteins that have to bind to the DNA, and each other, before the polymerase can begin transcription.

There are many steps along the way of protein synthesis and gene expression is regulated. Gene expression is when a gene in DNA is “turned on,” that is, used to make the protein it specifies. Not all the genes in your body are turned on at the same time or in the same cells or parts of the body.

For many genes, transcription is the key on/off control point: if a gene is not transcribed in a cell, it can’t be used to make a protein in that cell.

If a gene does get transcribed, it is likely going to be used to make a protein (i.e. expressed). In general (but not always) the more often a gene is transcribed, the more protein that will be made.

Various factors control how much a gene is transcribed. For instance, how tightly the DNA of the gene is wound around its supporting proteins to form chromatin can affect a gene’s availability for transcription.

Proteins called transcription factors, however, play a particularly central role in regulating transcription. These important proteins help determine which genes are active in each cell of your body.

Transcription Factors

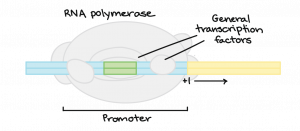

What has to happen for a gene to be transcribed? The enzyme RNA polymerase, which makes a new RNA molecule from a DNA template, must attach to the DNA of the gene. It attaches to a spot called the promoter.

The RNA polymerase can attach to the promoter only with the help of proteins called general transcription factors. They are part of the cell’s core transcription “toolkit,” needed for the transcription of any gene.

How do Transcription Factors Work?

Activators

Repressors

Turning Genes on in Specific Body Parts

Some genes need to be expressed in more than one body part or type of cell. For instance, suppose a gene needed to be turned on in your spine, skull, and fingertips, but not in the rest of your body. How can transcription factors make this pattern happen?

A gene with this type of pattern may have several enhancers (far-away clusters of binding sites for activators) or silencers (the same thing, but for repressors). Each enhancer or silencer may activate or repress the gene in a certain cell type or body part, binding transcription factors that are made in that part of the body.1,2

Example: Modular Mouse

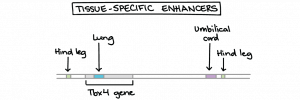

As an example, let’s consider a gene found in mice, called Tbx4. This gene is important for the development of many different parts of the mouse body, including the blood vessels and hind legs.3

During development, several well-defined enhancers drive Tbx4 expression in different parts of the mouse embryo. The diagram below shows some of the Tbx4 enhancers, each labeled with the body part where it produces expression.

Evolution of Development

Enhancers like those of the Tbx4 gene are called tissue-specific enhancers: they control a gene’s expression in a certain part of the body. Mutations of tissue-specific enhancers and silencers may play a key role in the evolution of body form.4

How could that work? Suppose that a mutation, or change in DNA, happened in the coding sequence of the Tbx4 gene. The mutation would inactivate the gene everywhere in the body and a mouse without a normal copy would likely die. However, a mutation in an enhancer might just change the expression pattern a bit, leading to a new feature (e.g., a shorter leg) without killing the mouse.

Transcription Factors and Cellular “Logic”

Can cells do logic? Not in the same way as your amazing brain. However, cells can detect information and combine it to determine the correct response—in much the same way that your calculator detects pushed buttons and outputs an answer.

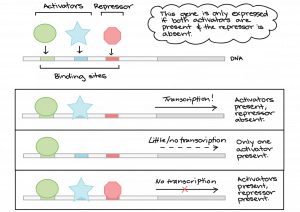

We can see an example of this “molecular logic” when we consider how transcription factors regulate genes. Many genes are controlled by several different transcription factors, with a specific combination needed to turn the gene on; this is particularly true in eukaryotes and is sometimes called combinatorial regulation.5,6 For instance, a gene may be expressed only if activators A and B are present, and if repressor C is absent.

- Activator A is present only in skin cells

- Activator B is active only in cells receiving “divide now!” signals (growth factors) from neighbors

- Repressor C is produced when a cell’s DNA is damaged

A Closer Look

After reading through this section, view the following video, which depicts many of the regulatory factors described above.

Examples

Now that you have learned some of the basics, check out this example that applies what you learned to a specific case study.

The video above briefly describes the laboratory part of this research. To learn more about what this research looks like, check out the “Stickleback Evolution Virtual Lab.”

Lactose Example

If you are still a little unsure of how switches work, then check out this HMMI Biointeractive interactive. The ability to digest lactose as an adult is a rare phenomenon in mammals. It evolved twice in humans—in Africa and Europe.

Exercise

Now let’s test your understanding of transcription regulation!

Take the quiz below the simulation as you work your way through it. Note that if you are using your mouse to scroll down, it may not work at this point—use the scrolling bar at the right edge of your web browser instead.

The Process of Transcription: A Detailed Look

This chapter began with an overview of transcription and then focused more deeply on the role of the polymerase and regulatory proteins. Now watch the following video. It is an in-depth version of the first video of this chapter, incorporating aspects described throughout this chapter.

References

-

Gilbert, S. F. (2000). Anatomy of the gene: Promoters and enhancers. In Developmental biology (6th ed.). Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK10023/#_A751_.

-

Gilbert, S. F. (2000). Silencers. In Developmental biology (6th ed.). Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK10023/#_A777_.

-

Menke, D. B., Guenther, C., and Kingsley, D. M. (2008). Dual hindlimb control elements in the Tbx4 gene and region-specific control of bone size in vertebrate limbs. Development, 135, 2543-2553. http://dx.doi.org/10.1242/dev.017384.

-

Wray, Gregory A. (2007). The evolutionary significance of cis-regulatory mutations. Nature Reviews Genetics, 8, 206-216. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrg2063.

-

Reece, J. B., Urry, L. A., Cain, M. L., Wasserman, S. A., Minorsky, P. V., and Jackson, R. B. (2011). Combinatorial control of gene activation. In Campbell Biology (10th ed., pp. 37). San Francisco, CA: Pearson.

-

Reményi, Attila, Hans R. Schöler, and Matthias Wilmanns. (2004). Combinatorial control of gene expression. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, 11(9), 812. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nsmb820. Retrieved from http://www.nature.com/scitable/content/Combinatorial-control-of-gene-expression-16976.

Attributions

This chapter is a modified derivative of the following articles:

“Regulated Transcription” by Molecular and Cellular Biology Learning Center, Virtual Cell Animation Collection, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

“Transcription” by Molecular and Cellular Biology Learning Center, Virtual Cell Animation Collection, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

“Transcription Factors” by Khan Academy, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. All Khan Academy content is available for free at (www.khanacademy.org).

Media Attributions

- Central Dogma (Transcription) © Andrea Bierema

- general transcription factors © Khan Academy is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- activator © Khan Academy is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- repressors © Khan Academy is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- binding sites © Khan Academy is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- enhancers © Khan Academy is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- activators and repressors © Khan Academy is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license